The NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope has photographed the farthest-discovered active inbound comet, C/2017 K2 (PANSTARRS). The comet’s orbit indicates that it came from the Oort Cloud, a spherically shaped reservoir almost a light-year in diameter containing leftovers from the formation of our Solar System 4.6 billion years ago.

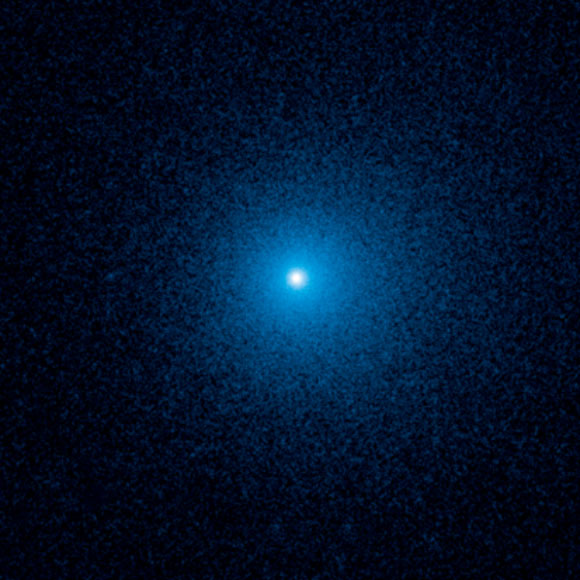

This Hubble image shows a fuzzy cloud of dust, called a coma, surrounding the comet C/2017 K2 PANSTARRS (K2), the farthest active comet ever observed entering the Solar System. Image credit: NASA / ESA / D. Jewitt, University of California, Los Angeles.

C/2017 K2 (PANSTARRS), or ‘K2,’ was discovered on May 21, 2017 by the Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System (Pan-STARRS) in Hawaii.

Slightly warmed by the remote Sun, K2 has already begun to develop an 80,000-mile-wide fuzzy cloud of dust, called a coma.

Dr. David Jewitt of the University of California, Los Angeles, and his colleagues used Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3 at the end of June to take a closer look at the icy visitor.

“K2 is so far from the Sun and so cold, we know for sure that the activity — all the fuzzy stuff making it look like a comet — is not produced, as in other comets, by the evaporation of water ice,” Dr. Jewitt explained.

“Instead, we think the activity is due to the sublimation of super-volatiles as K2 makes its maiden entry into the Solar System’s planetary zone. That’s why it’s special. This comet is so far away and so incredibly cold that water ice there is frozen like a rock.”

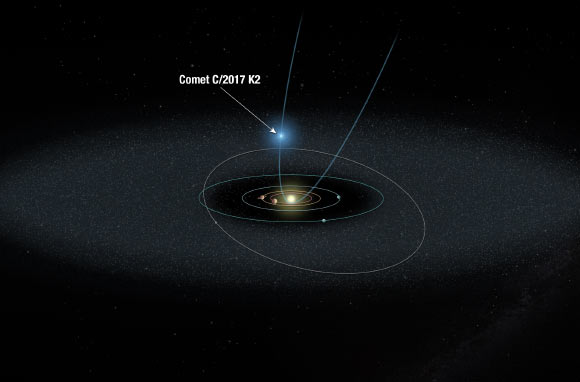

This illustration shows the orbit of K2 on its maiden voyage into the Solar System. Hubble observed tis comet when it was 1.5 billion miles from the Sun, halfway between the orbits of Saturn and Uranus. The farthest object from the Sun depicted here is the dwarf planet Pluto, which resides in the Kuiper Belt, a vast rim of primordial debris encircling our Solar System. Image credit: NASA / ESA / A. Field, STScI.

Based on the Hubble observations of K2’s coma, the astronomers suggest that sunlight is heating frozen volatile gases — such as oxygen, nitrogen, carbon dioxide, and carbon monoxide — that coat the comet’s frigid surface. These icy volatiles lift off from the comet and release dust, forming the coma.

“I think these volatiles are spread all through K2, and in the beginning billions of years ago, they were probably all through every comet presently in the Oort Cloud,” Dr. Jewitt said.

“But the volatiles on the surface are the ones that absorb the heat from the Sun, so, in a sense, the comet is shedding its outer skin.”

“Most comets are discovered much closer to the Sun, near Jupiter’s orbit, so by the time we see them, these surface volatiles have already been baked off. That’s why I think K2 is the most primitive comet we’ve seen.”

Hubble’s sharp ‘eye’ also helped the team estimate the size of K2’s nucleus — less than 12 miles across — though the tenuous coma is 10 Earth diameters across.

“This vast coma must have formed when the comet was even farther away from the Sun,” the astronomers said.

The team’s findings are published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters (arXiv.org preprint).

_____

David Jewitt et al. 2017. A comet active beyond the crystallization zone. ApJL 847, L19; doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/aa88b4