Astronomers have used data gathered by K2, the second mission of NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope, to confirm details of TRAPPIST-1h, the outermost of seven Earth-size exoplanets orbiting the star TRAPPIST-1.

TRAPPIST-1 is an ultracool dwarf star in the constellation Aquarius, 38.8 light-years away.

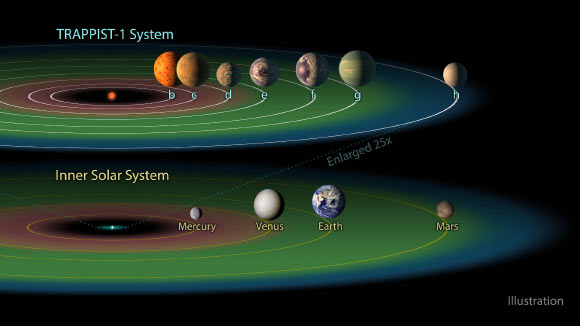

In February 2017, astronomers announced that the star hosts at least seven planets — TRAPPIST-1b, c, d, e, f, g and h.

All these planets are similar in size to Earth and Venus, or slightly smaller, and have very short orbital periods.

Now, an international team of astronomers, led by Rodrigo Luger, a doctoral student at the University of Washington, Seattle, has confirmed that the outermost planet, TRAPPIST-1h, orbits its host star every 18.77 days, is linked in its orbital path to its siblings and is frigidly cold.

Far from TRAPPIST-1, the planet is likely uninhabitable — but it may not always have been so.

“TRAPPIST-1h was exactly where our team predicted it to be,” said Luger, who is lead author on a paper published this week in the journal Nature Astronomy.

The TRAPPIST-1 system contains a total of seven Earth-size planets. Three of them — TRAPPIST-1e, f and g — dwell in their star’s so-called ‘habitable zone.’ Image credit: NASA.

The team discovered a mathematical pattern in the orbital periods of the inner six planets, which was strongly suggestive of an 18.77 day period for TRAPPIST-1h.

The astronomers studied the TRAPPIST-1 system more closely using 79 days of observation data from K2.

They were able to observe and study four transits of TRAPPIST-1h across its star.

They also used the K2 data to further characterize the orbits of the other six planets, help rule out the presence of additional transiting planets, and determine the rotation period and activity level of the star.

They discovered that TRAPPIST-1’s planets appear linked in a complex dance known as an orbital resonance where their respective orbital periods are mathematically related and slightly influence each other.

“These orbital connections were forged early in the life of the TRAPPIST-1 system, when the planets and their orbits were not fully formed,” Luger said.

“The resonant structure is no coincidence, and points to an interesting dynamical history in which the planets likely migrated inward in lock-step. This makes the system a great testbed for planet formation and migration theories.”

It also means that while TRAPPIST-1h is now extremely cold — with an average temperature of minus 148 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 100 degrees Celsius) — it likely spent several hundred million years in a much warmer state, when its host star was younger and brighter.”

“We could therefore be looking at a planet that was once habitable and has since frozen over, which is amazing to contemplate and great for follow-up studies,” Luger said.

_____

Rodrigo Luger et al. 2017. A seven-planet resonant chain in TRAPPIST-1. Nature Astronomy 1, article number: 0129; doi: 10.1038/s41550-017-0129