A team of astronomers from NASA’s exoplanet-hunting Kepler mission has released a new catalog of transiting planet candidates.

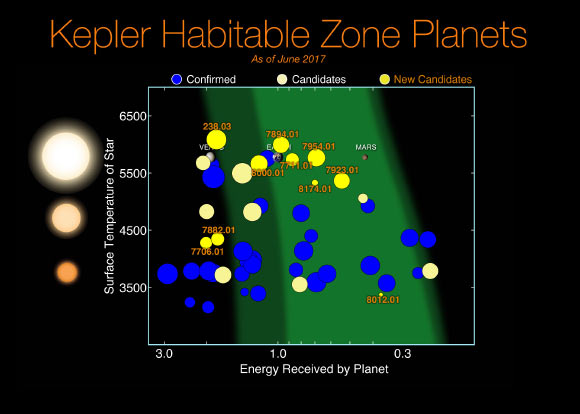

The new Kepler catalog introduces 219 new candidate planets, 10 of which are near-Earth size and orbiting in their host star’s habitable zone.

This is the eighth release of the Kepler candidate catalog, gathered by reprocessing the entire set of data from Kepler’s observations during the first four years of its primary mission.

The data will serve as the foundation for more study to determine the prevalence and demographics of planets in our Milky Way Galaxy.

It’s also the final catalog from Kepler’s view of the patch of sky in the constellation Cygnus.

“The Kepler data set is unique, as it is the only one containing a population of near Earth-analogs — planets with roughly the same size and orbit as Earth,” said Kepler program scientist Dr. Mario Perez, from the Astrophysics Division of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate.

“Understanding their frequency in the galaxy will help inform the design of future NASA missions to directly image another Earth.”

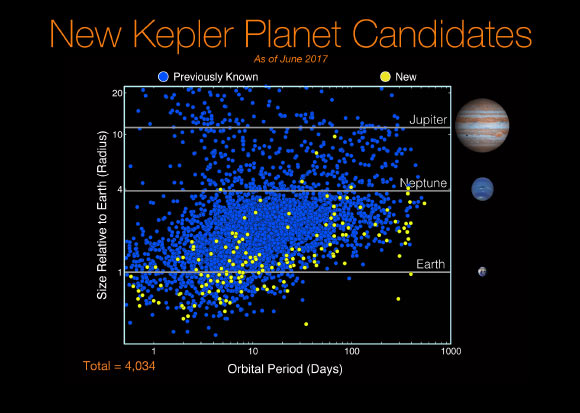

With the release of this catalog, derived from data publicly available on the NASA Exoplanet Archive, there are now 4,034 planet candidates identified by the Kepler telescope. Of which, 2,335 have been verified as exoplanets.

Of roughly 50 near-Earth size habitable zone candidates detected by Kepler, more than 30 have been verified.

“This carefully-measured catalog is the foundation for directly answering one of astronomy’s most compelling questions — How many planets like our Earth are in the Galaxy?” said Dr. Susan Thompson, Kepler research scientist at the SETI Institute and co-author of the catalog study.

There are 4,034 planet candidates now known with the release of the eighth Kepler planet candidate catalog. Of these, 2,335 have been confirmed as planets. The blue dots show planet candidates from previous catalogs, while the yellow dots show new candidates from the eighth catalog. New planet candidates continue to be found at all periods and sizes due to continued improvement in detection techniques. Notably, 10 of these new candidates are near-Earth-size and at long orbital periods, where they have a chance of being rocky with liquid water on their surface. Image credit: NASA / Ames Research Center / Wendy Stenzel.

Highlighted are new planet candidates from the eighth Kepler planet candidate catalog that are less than twice the size of Earth and orbit in the stars’ habitable zone. The dark green area represents an optimistic estimate for the habitable zone, while the brighter green area represents a more conservative estimate for the habitable zone. The candidates are plotted as a function of their stars’ surface temperature on the vertical axis and by the amount of energy the planet candidate receives from its host star on the horizontal axis. Brighter yellow circles show new planet candidates in the eighth catalog, while pale yellow circles show planet candidates from previous catalogs. Blue circles represent candidates that have been confirmed as planets due to follow-up observations. The sizes of the colored disks indicate the sizes of these exoplanets relative to one another and to the image of Earth, Venus and Mars, placed on this diagram for reference. Note that the new candidates tend to be around stars more similar to the Sun — around 5,800 degrees Kelvin — representing progress in finding planets that are similar to the Earth in size and temperature that orbit Sun-like stars. Image credit: NASA / Ames Research Center / Wendy Stenzel.

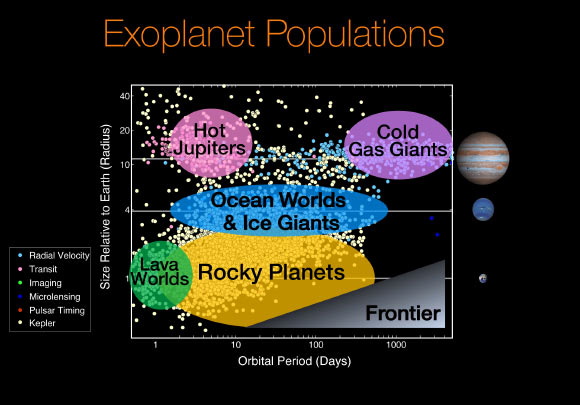

The population of exoplanets detected by the Kepler mission (yellow dots) compared to those detected by other surveys using various methods: radial velocity (light blue dots), transit (pink dots), imaging (green dots), microlensing (dark blue dots), and pulsar timing (red dots). For reference, the horizontal lines mark the sizes of Jupiter, Neptune and Earth, all of which are displayed on the right side of the diagram. The colored ovals denote different types of planets: hot Jupiters (pink), cold gas giants (purple), ocean worlds and ice giants (blue), rocky planets (yellow), and lava worlds (green). The shaded gray triangle at the lower right marks the exoplanet frontier that will be explored by future exoplanet surveys. Image credit: NASA / Ames Research Center / Natalie Batalha / Wendy Stenzel.

To ensure a lot of planets weren’t missed, Dr. Perez, Dr. Thompson and co-authors introduced their own simulated planet transit signals into the data set and determined how many were correctly identified as planets.

Then, they added data that appear to come from a planet, but were actually false signals, and checked how often the analysis mistook these for planet candidates.

This work told them which types of planets were overcounted and which were undercounted by the Kepler team’s data processing methods.

_____

Steve Bryson et al. 2017. Determining Statistically Optimal Metric Thresholds for the Final Kepler Planet Candidate Catalog. AAS Meeting 230, abstract #102.03