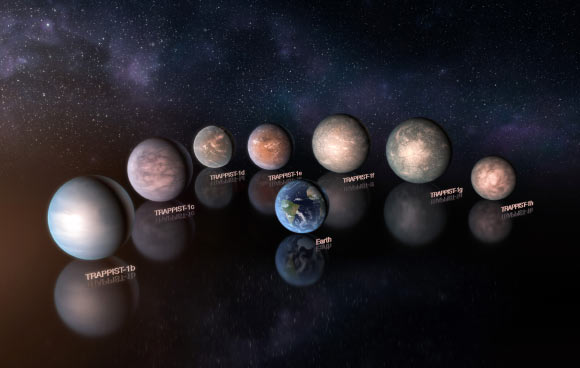

A new study has found that planets orbiting TRAPPIST-1, an ultracool dwarf star 38.8 light-years away in the constellation Aquarius, are mostly made of rock, with up to 5% of their mass in the form of water — about 250 times more than Earth’s oceans. The results are published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

This artist’s impression compares TRAPPIST-1 planets to the Earth at the same scale. Image credit: M. Kornmesser / ESO.

In February 2017 astronomers announced the discovery of seven Earth-sized planets orbiting TRAPPIST-1.

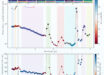

Following up on the discovery, an international team of scientists led by University of Bern astronomer Simon Grimm used several ground- and space-based telescopes to determine the planets’ densities more precisely than ever.

“The TRAPPIST-1 planets are so close together that they interfere with each other gravitationally, so the times when they pass in front of the star shift slightly. These shifts depend on the planets’ masses, their distances and other orbital parameters,” Dr. Grimm explained.

“With a computer model, we simulate the planets’ orbits until the calculated transits agree with the observed values, and hence derive the planetary masses.”

The measurements of the densities, when combined with models of the planets’ compositions, strongly suggest that the seven TRAPPIST-1 planets are not barren rocky worlds.

They seem to contain significant amounts of volatile material, probably water, amounting to up to 5% the planet’s mass in some cases — a significant amount; by comparison the Earth has only about 0.02% water by mass.

“Densities, while important clues to the planets’ compositions, do not say anything about habitability,” said co-author Dr. Brice-Olivier Demory, a researcher at the University of Bern.

“However, our study is an important step forward as we continue to explore whether these planets could support life.”

The innermost planets, TRAPPIST-1b and c, are likely to have rocky cores and be surrounded by atmospheres much thicker than Earth’s.

TRAPPIST-1d, meanwhile, is the lightest of the planets at about 30% the mass of Earth. Scientists are uncertain whether it has a large atmosphere, an ocean or an ice layer.

TRAPPIST-1e is the only planet in the system slightly denser than Earth. It may have a denser iron core and does not necessarily have a thick atmosphere, ocean or ice layer.

It is mysterious that TRAPPIST-1e appears to be so much rockier in its composition than the rest of the planets. In terms of size, density and the amount of radiation it receives from its star, this is the planet that is most similar to Earth.

TRAPPIST-1f, g and h are far enough from the host star that water could be frozen into ice across their surfaces. If they have thin atmospheres, they would be unlikely to contain the heavy molecules that we find on Earth, such as carbon dioxide.

“It is interesting that the densest planets are not the ones that are the closest to the star, and that the colder planets cannot harbor thick atmospheres,” said co-author Dr. Caroline Dorn, a scientist at the University of Zurich.

_____

S. Grimm et al. The nature of the TRAPPIST-1 exoplanets. A&A, in press; doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201732233