Microbiologists from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have discovered that different groups of marine microbes can work together to obtain nutrition from their surroundings.

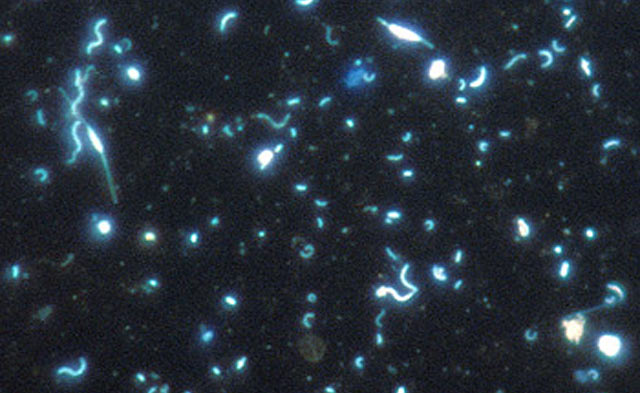

Despite the amazing diversity of marine microbes, the scientists find that many different groups work together to obtain nutrition (© Ed DeLong / MBARI)

The open ocean contains an amazing diversity of extremely tiny organisms called picoplankton. This group includes relatively simple life forms such as marine bacteria, as well as more complicated organisms. Some picoplankton obtain energy from sunlight through photosynthesis, just as plants do. Others, called heterotrophs, eat other picoplankton or consume organic compounds in seawater.

The MBARI and MIT scientists used cutting-edge genomic research to show how these infinitesimal creatures react in synchrony to changes in their environment.

They collected samples of seawater and microbes every four hours for two days straight, using a drifting version of the Environmental Sample Processor (ESP). The ESP was suspended from a large buoy that drifted across the waters offshore of Monterey Bay. This means that all of the samples were taken from a single community of picoplankton as these organisms drifted with the ocean currents.

“We’ve essentially captured a day in the life of these microbes,” said Dr Ed DeLong of the MIT, senior author of the study appearing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

After returning the samples to the laboratory, the researchers used cutting-edge lab techniques to figure out which genes within the microbes were actively being used at different times of day. This involved sorting through millions of billions of fragments of genetic material and then assigning each fragment to a specific gene and a specific type of microbe.

The study showed that some groups of genes were expressed repeatedly at specific times of day. For example, genes involved in photosynthesis were most active in the morning, when the photosynthetic microbes ramped up their light-gathering activities.

More surprising was the discovery that a variety of genes in very different groups of heterotrophic picoplankton – groups as different as humans and fungi – were expressed more or less in unison. Most of these genes were related to cell growth and nutrient processing. The team hypothesized that all these microbes were reacting to the same environmental changes, but that different groups of microbes were responding in different ways.

Although the researchers cannot tell exactly which environmental changes the microbes were responding to, they suspect that the different groups of microbes were working together to obtain different types of food. For example, some picoplankton could have been consuming large organic compounds such as proteins and fats. In the process, they could have produced simpler organic compounds, such as amino acids, which were then released into the surrounding seawater and consumed by other picoplankton.

These results show a surprising amount of coordination between marine microbes. They also suggest that, as in the food webs of larger organisms, many different groups of marine microbes rely on each other to survive on a day-to-day basis. This could help explain why so many species of marine microbes are difficult or impossible to grow by themselves in the laboratory.

_______

Bibliographic information: Ottesen EA et al. 2013. Pattern and synchrony of gene expression among sympatric marine microbial populations. PNAS, vol. 110, no. 6, E488-E497; doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222099110