The question of how the human brain recognizes the faces of familiar individuals has been important throughout the history of neuroscience. Cells linking visual processing to the person’s memory have been proposed, but not found. Now, a team of U.S. neuroscientists has discovered such cells in the brain’s temporal pole region; these cells responded to faces when they were personally familiar.

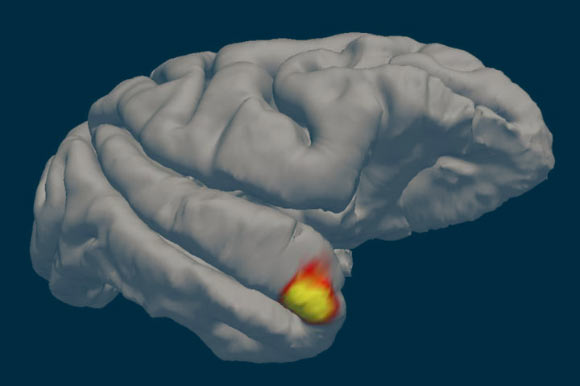

An area (red-yellow) in the brain’s temporal pole specializes in familiar face recognition. Image credit: Sofia Landi.

The idea of the so-called grandmother neuron — a single cell at the crossroads of sensory perception and memory, capable of prioritizing an important face over the rabble — first showed up in the 1960s.

One neuron for the memory of one’s grandmother, another to recall one’s mother, and so on. At its heart, the notion of a one-to-one ratio between brain cells and objects or concepts was an attempt to tackle the mystery of how the brain combines what we see with our long-term memories.

Neuroscientists have since discovered plenty of sensory neurons that specialize in processing facial information, and as many memory cells dedicated to storing data from personal encounters.

But a grandmother neuron — or even a hybrid cell capable of linking vision to memory — never emerged.

“The expectation is that we would have had this down by now. Far from it! We had no clear knowledge of where and how the brain processes familiar faces,” said Professor Winrich Freiwald, a neuroscientist in the Laboratory of Neural Systems at the Rockefeller University and the Center for Brains, Minds & Machines.

Recently, Professor Freiwald and his colleagues discovered that a small area in the brain’s temporal pole region may be involved in facial recognition.

So they used functional magnetic resonance imaging as a guide to zoom in on the temporal pole regions of two rhesus monkeys, and recorded the electrical signals of temporal pole neurons as the macaques watched images of familiar faces and unfamiliar faces that they had only seen virtually, on a screen.

They found that neurons in the temporal pole region were highly selective, responding to faces that the subjects had seen before more strongly than unfamiliar ones.

And the neurons were fast, discriminating between known and unknown faces immediately upon processing the image.

Interestingly, these cells responded threefold more strongly to familiar over unfamiliar faces even though the subjects had in fact seen the unfamiliar faces many times virtually, on screens.

“This may point to the importance of knowing someone in person,” said Dr. Sofia Landi, a neuroscientist in the Laboratory of Neural Systems at the Rockefeller University and the Department of Physiology and Biophysics at the University of Washington.

“Given the tendency nowadays to go virtual, it is important to note that faces that we have seen on a screen may not evoke the same neuronal activity as faces that we meet in-person.”

The findings constitute the first evidence of a hybrid brain cell, not unlike the fabled grandmother neuron.

The cells of the temporal pole region behave like sensory cells, with reliable and fast responses to visual stimuli.

But they also act like memory cells which respond only to stimuli that the brain has seen before — in this case, familiar individuals — reflecting a change in the brain as a result of past encounters.

“They’re these very visual, very sensory cells — but like memory cells. We have discovered a connection between the sensory and memory domains,” Professor Freiwald said.

The findings were published in the journal Science.

_____

Sofia M. Landi et al. A fast link between face perception and memory in the temporal pole. Science, published online July 1, 2021; doi: 10.1126/science.abi6671