A small new study published in the Journal of Avian Biology shows that songbirds migrating from Scandinavia to Africa in the autumn occasionally fly as high as 13,000 feet (4 km), probably adjusting their flight to take advantage of favorable winds and different wind layers.

The aim of the study was to investigate whether the measuring method itself works on small birds, that is, to measure acceleration, barometric pressure and temperature throughout the flight using a small data logger attached to the bird.

The data logger was attached to two individuals of different species. Among other things, the results show how long it takes for each bird to fly to their destination.

“We only followed two individuals and two species. But the fact that both of them flew so high does surprise me,” said Dr. Sissel Sjöberg, a biologist at Lund University and the Zoological Museum in Copenhagen.

“It’s fascinating and it raises new questions about the physiology of birds. How do they cope with the air pressure, thin air and low temperatures at these heights?”

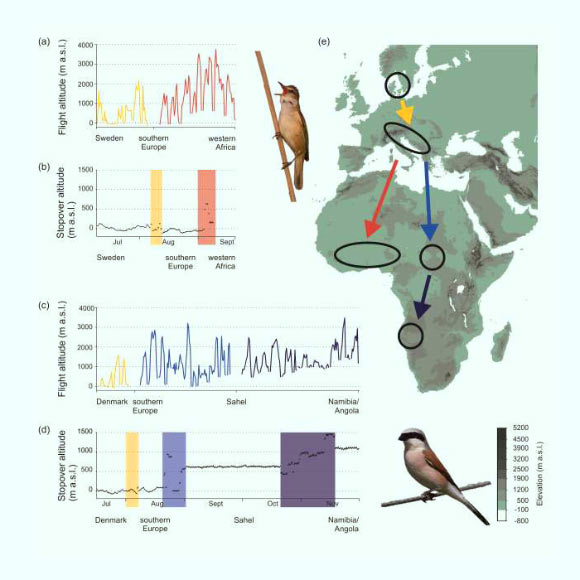

Dr. Sjöberg and colleagues tracked one individual of the red-backed shrike (Lanius collurio) and one great reed warbler (Acrocephalus arundinaceus) along their autumn migration. Both these species breed in Europe and winter in sub-Saharan Africa.

Both individuals performed their migration stepwise in travel segments and climbed most feet during the passage across the Mediterranean Sea and the Sahara Desert and least feet during the first flight segment in Europe.

Flight altitudes, and altitudes of stationary periods, in a great reed warbler (a-b) and a red-backed shrike (c-d). Image credit: Sjöberg et al, doi: 10.1111/jav.01821.

The great reed warbler reached its highest flight altitude of 12,960 feet (3,950 m) above sea level during the travel segment from Europe to West Africa, while the red-backed shrike reached 11,975 feet (3,650 m) as maximum flight altitude during its travel segment from Sahel to southern Africa.

Both individuals used both lowlands and highlands for resting periods along their migrations.

“It’s likely that other small birds fly as high, maybe even higher. But there is no evidence of that yet,” Dr. Sjöberg said.

“In this study, we only worked with data collected during the autumn, when the small birds migrate to Africa.”

“There are other studies that indicate that the birds fly even higher when they migrate back in the spring, but we cannot say for sure.”

_____

Sissel Sjöberg et al. Barometer logging reveals new dimensions of individual songbird migration. Journal of Avian Biology, published online June 29, 2018; doi: 10.1111/jav.01821