Previously thought to be ocean surface dwellers, box rays (Mobula tarapacana) can dive to depths of 2,000 meters, according to a team of scientists from Portugal, Saudi Arabia and the United States led by Dr Simon Thorrold of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

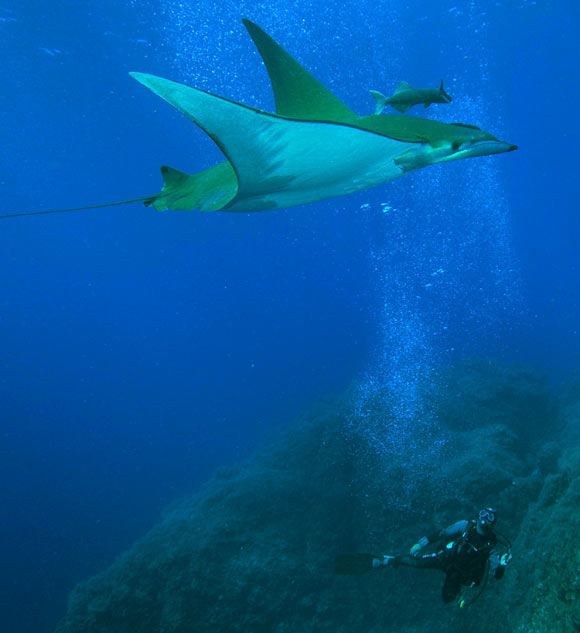

This image shows the box ray (Mobula tarapacana). Image credit: Jorge Fontes / Institute of Marine Research / Laboratory of Robotics and Systems in Engineering and Science.

The box ray, also known as the Chilean devil ray, the Greater Guinean mobula or the Spiny mobula, is a species of fish in the Myliobatidae family.

These rays are ocean nomads traveling large areas of the ocean.

“We thought they probably traveled long distances horizontally, but we had no idea that they were diving so deep. That was truly a surprise,” Dr Thorrold said.

Dr Thorrold and his colleagues used transmitting tags to record the movement patterns of 15 box rays in the central North Atlantic Ocean during 2011 and 2012. These tags measured water temperature, depth, and light levels of the waters.

The dive data showed box rays routinely descended at speeds up to 6 m per second to depths of almost 2,000 m in water temperatures less than 4 degrees Celsius.

The dives generally followed two distinct patterns. The most common involved descent to the maximum depth followed by a slower, stepwise return to the surface with a total dive time of 60 to 90 minutes. The rays generally only made one such dive during a 24-hour period.

In the second dive pattern, the box rays descended and then remained at depths of up to 1,000 meters for as long as 11 hours.

Box rays, also known as Chilean devil rays, are actually among the deepest-diving ocean animals. Image credit: Jack Cook / Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

During the day, the rays would spend time up at the surface – presumably heating up – immediately before, and then again, after a deep dive. How else might these animals be dealing with the cold temperatures of the deep ocean?

Previous research found that several species of rays possess a physiological adaptation – well-developed blood vessels around the cranial cavity that essentially serve as heat exchange systems. At the time, it was hypothesized that the rays must be using this adaptation to cool down rather than warm up.

“Rays were always seen in very warm water up at the surface, so why would they need an adaptation for cold water? Once we looked at the dive data from the tags, of course it made perfect sense that the rays have these systems. Sometimes they’re down diving for two or three hours in very cold water – 2 to 3 degrees Celsius,” said Dr Thorrold, who is the first author of a paper published in the journal Nature Communications.

While it’s not certain what the rays are doing at these depths, the dive profiles suggest that they’re foraging on large numbers of fish that live in deeper waters.

______

Simon R. Thorrold et al. 2014. Extreme diving behaviour in devil rays links surface waters and the deep ocean. Nature Communications 5, article number: 4274; doi: 10.1038/ncomms5274