Researchers from the University of Massachusetts, Johns Hopkins Children’s Center and the University of Mississippi have reported about the first case of a functional cure in an HIV-infected infant.

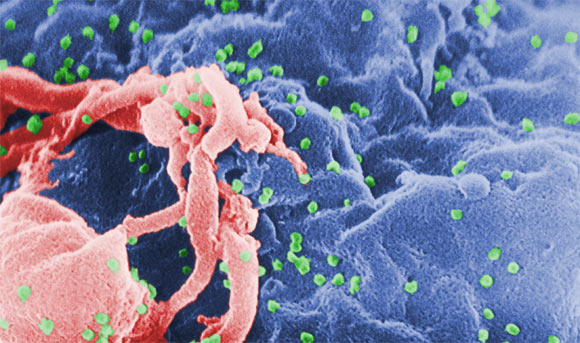

Scanning electron micrograph of HIV-1, shown in green, budding from cultured lymphocyte (C. Goldsmith)

The results, presented on March 3 at the 20th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in Atlanta, may help pave the way to eliminating HIV infection in children.

The infant described in the report underwent remission of HIV infection after receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART) within 30 hours of birth. “The prompt administration of antiviral treatment likely led to this infant’s cure by halting the formation of hard-to-treat viral reservoirs – dormant cells responsible for reigniting the infection in most HIV patients within weeks of stopping therapy,” the researchers said.

“Prompt antiviral therapy in newborns that begins within days of exposure may help infants clear the virus and achieve long-term remission without lifelong treatment by preventing such viral hideouts from forming in the first place,” said lead author Dr Deborah Persaud, a virologist with Johns Hopkins Children’s Center.

The team believes this is precisely what happened in the child described in the report. That infant is now deemed ‘functionally cured,’ a condition that occurs when a patient achieves and maintains long-term viral remission without lifelong treatment and standard clinical tests fail to detect HIV replication in the blood. In contrast to a sterilizing cure – a complete eradication of all viral traces from the body – a functional cure occurs when viral presence is so minimal, it remains undetectable by standard clinical tests, yet discernible by ultrasensitive methods.

The child was born to an HIV-infected mother and received combination antiretroviral treatment beginning 30 hours after birth. A series of tests showed progressively diminishing viral presence in the infant’s blood, until it reached undetectable levels 29 days after birth. “The infant remained on antivirals until 18 months of age, at which point the child was lost to follow-up for a while and,” the researchers said, “stopped treatment.” Ten months after discontinuation of treatment, the child underwent repeated standard blood tests, none of which detected HIV presence in the blood. Test for HIV-specific antibodies – the standard clinical indicator of HIV infection – also remained negative throughout.

Currently, high-risk newborns receive a combination of antivirals at prophylactic doses to prevent infection for six weeks and start therapeutic doses if and once infection is diagnosed. “But this particular case,” the scientists said, “may change the current practice because it highlights the curative potential of very early ART.”

Natural viral suppression without treatment is an exceedingly rare phenomenon observed in less than half a percent of HIV-infected adults, known as ‘elite controllers,’ whose immune systems are able to rein in viral replication and keep the virus at clinically undetectable levels. HIV experts have long sought a way to help all HIV patients achieve elite-controller status. “The new case,” the researchers said, “may be that long-sought game-changer because it suggests prompt ART in newborns can do just that.”

The investigators caution they don’t have enough data to recommend change right now to the current practice of treating high-risk infants with prophylactic, rather than therapeutic, doses but the infant’s case provides the rationale to start proof-of-principle studies in all high-risk newborns.

“Our next step is to find out if this is a highly unusual response to very early antiretroviral therapy or something we can actually replicate in other high-risk newborns,” Dr Persaud said.

“Complete viral eradication on a large scale is our long-term goal but, for now, remains out of reach, and our best chance may come from aggressive, timely and precisely targeted use of antiviral therapies in high-risk newborns as a way to achieve functional cure,” said senior author Prof Katherine Luzuriaga, an immunologist with the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

“Despite the promise this approach holds for infected newborns, preventing mother-to-child transmission remains the primary goal.”

“Prevention really is the best cure, and we already have proven strategies that can prevent 98 percent of newborn infections by identifying and treating HIV-positive pregnant women,” said co-author Prof Hannah Gay of the University of Mississippi Medical Center, the HIV expert who treated the infant.

______

Bibliographic information: Deborah Persaud et al. Functional HIV Cure after Very Early ART of an Infected Infant. 20th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in Atlanta, paper #48LB