Neuronal loss in Alzheimer’s disease may be the result of a cell quality control mechanism trying to protect the brain from the accumulation of malfunctioning neurons, according to new research published in the journal Cell Reports.

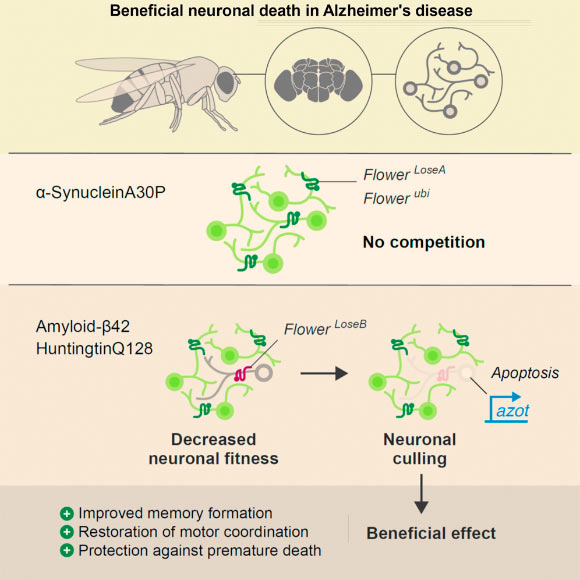

Multicellular organisms eliminate abnormal but viable cells based on their fitness status through cell competition to maintain tissue integrity. Coelho et al report that fitness-based neuronal selection occurs in the course of neurodegeneration. Death of unfit neurons is beneficial, protecting against disease progression by restoring motor and cognitive functions. Image credit: Coelho et al, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.11.098.

The cell quality control mechanism at play is called cell competition. It leads to the selection of the fittest cells in a tissue by enabling a ‘fitness comparison’ between each cell and its neighbors — with the fitter cells then triggering the suicide of less fit ones.

In 2015, Dr. Eduardo Moreno of the Champalimaud Centre for the Unknown and the University of Bern and his colleagues discovered that clearing unfit cells from a tissue was a very important anti-aging mechanism to preserve organ function.

The researchers reasoned that, if these fitness comparisons happened in normal aging, they could also be involved in neurodegenerative diseases associated with accelerated aging, such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s or Huntington’s disease.

In the new study, they bred fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster) that had been genetically manipulated to express in their brain amyloid-beta, a protein that forms aggregates in the brains of Alzheimer’s disease patients.

“The transgenic flies displayed symptoms and pathologies similar to those of Alzheimer’s disease patients,” said Dr. Christa Rhiner, also from the Champalimaud Centre for the Unknown and the University of Bern.

“The flies showed loss of long-term memory, accelerated aging of the brain and motor coordination problems, all of which got worse with age.”

The first thing the scientists wanted to do was to see whether in these flies, neuronal death was indeed activated by the process of fitness comparison.

“In other words, that the neurons were not dying on their own but being killed by fitter neighbors,” Dr. Moreno said.

“When we started, the current view was that neuronal death must be always detrimental. And much to our surprise, we found that neuronal death actually counteracts the disease,” said Dr. Dina Coelho, also from the Champalimaud Centre for the Unknown and the University of Bern.

“What happened was that when we blocked neuronal death in the flies’ brain, the insects developed even worse memory problems, worse motor coordination problems, died earlier and their brain degenerated faster.”

“However, when we boosted the fitness comparison process, thus accelerating the death of unfit neurons, the flies expressing amyloid-beta proteins showed an impressive recovery.”

“The flies almost behaved like normal flies with regard to memory formation, locomotive behavior and learning, and this at a time point where the Alzheimer’s disease flies were already strongly affected,” Dr. Rhiner said.

“This means that the anti-aging mechanism in question keeps working well in Alzheimer’s disease and shows that, in fact, the neuronal death protects the brain from more widespread damage and therefore the neuronal loss is not what is bad, it is worse not to let those neurons die,” Dr. Moreno said.

“Our most important finding is that we have probably been thinking the wrong way about Alzheimer’s disease. Our results suggest that neuronal death is beneficial because it removes neurons that are affected by noxious beta-amyloid aggregates from brain circuits, and having those dysfunctional neurons is worse than losing them.”

_____

Dina S. Coelho et al. 2018. Culling Less Fit Neurons Protects against Amyloid-β-Induced Brain Damage and Cognitive and Motor Decline. Cell Reports 25 (13): 3661-3673; doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.11.098