According to a study published today in the journal Nature Communications, a recently discovered species of early human ancestor called Australopithecus sediba didn’t have the jaw and tooth structure necessary to exist on a steady diet of hard foods.

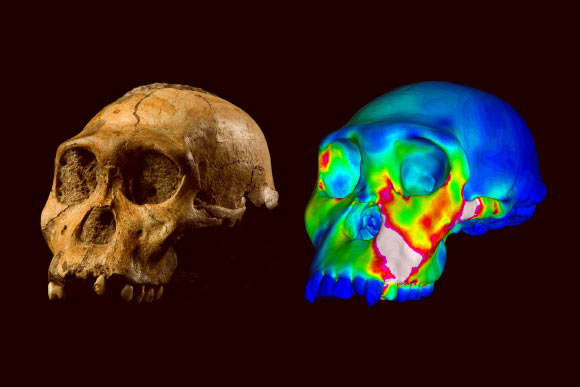

The fossilized skull of Australopithecus sediba specimen MH1 and a finite element model of its cranium depicting strains experienced during a simulated bite on its premolars: ‘warm’ colors indicate regions of high strain, ‘cool’ colors indicate regions of low strain. Image credit: Brett Eloff / Lee Berger / University of the Witwatersrand.

Discovered in 2008, Australopithecus sediba is a small hominin that lived about 2 million years ago in what is now South Africa, related to other australopiths and early Homo species.

Australopiths appear in the fossil record approximately 4 million years ago, and although they have some human traits like the ability to walk upright on two legs, most of them lack other characteristically human features like a large brain, flat faces with small jaws and teeth, and advanced tool-use.

Humans in the genus Homo are almost certainly descended from an australopith ancestor, and Australopithecus sediba is a candidate to be either that ancestor or something similar to it.

“Most australopiths had amazing adaptations in their jaws, teeth and faces that allowed them to process foods that were difficult to chew or crack open,” said Prof. David Strait of Washington University in St. Louis, who is the senior author on the study.

“Among other things, they were able to efficiently bite down on foods with very high forces,” he said.

“Australopithecus sediba has been hypothesized to be a close relative of the genus Homo,” Prof. Strait and co-authors said. “We show that MH1, the type specimen of A. sediba, was not optimized to produce high molar bite force and appears to have been limited in its ability to consume foods that were mechanically challenging to eat.”

The study describes biomechanical testing of a computer-based model of the MH1 skull. It does not directly address whether Australopithecus sediba is indeed a close evolutionary relative of early Homo, but it does provide further evidence that dietary changes were shaping the evolutionary paths of early humans.

“Humans also have this limitation on biting forcefully and we suspect that early Homo had it as well, yet the other australopiths that we have examined are not nearly as limited in this regard,” said study lead author Dr. Justin Ledogar, of the University of New England, Australia.

“This means that whereas some australopith populations were evolving adaptations to maximize their ability to bite powerfully, others — including Australopithecus sediba — were evolving in the opposite direction.”

“Some of these ultimately gave rise to Homo. Thus, a key to understanding the origin of our genus is to realize that ecological factors must have disrupted the feeding behaviors and diets of australopiths,” Prof. Strait said.

“Diet is likely to have played a key role in the origin of Homo.”

_____

Justin A. Ledogar et al. 2016. Mechanical evidence that Australopithecus sediba was limited in its ability to eat hard foods. Nature Communications 7, article number: 10596; doi: 10.1038/ncomms10596