During the Upper Paleolithic, lions become an important theme in Paleolithic art and are more frequent in anthropogenic faunal assemblages. However, the relationship between hominins and lions in earlier periods is poorly known and primarily interpreted as interspecies competition. In a paper published in the journal Scientific Reports, paleoanthropologists present evidence of hunting lesions on the 48,000-year-old skeleton of a cave lion found at Siegsdorf, Germany, that attest to the earliest direct instance of a large predator kill in human history. The authors also present the discovery of lion phalanges at least 190,000 years old from Einhornhöhle, Germany, representing the earliest example of the use of cave lion skin by Neanderthals in Central Europe.

Neanderthals butchering the freshly killed cave lion from Siegsdorf, Germany. Image credit: Julio Lacerda / NLD.

Among all the large predators we have encountered during our evolutionary journey, the lion is arguably one of the most charismatic. To this day, it continues to be an icon of popular culture in many traditions worldwide.

The story of the lion’s dispersal shares some parallels with that of our own. The lion lineage originated in eastern Africa, with the earliest fossils of lion-like Panthera dated between 3.8 and 3.6 million years at Laeotoli, Tanzania.

A remarkably rapid dispersal occurred during the Middle Pleistocene, as evidenced by the presence of lion (Panthera fossilis) remains in Western Europe. By the Late Pleistocene, the Eurasian cave lion (Panthera spelaea) occupied the key ecological role of apex predator until its extinction by the end of the Pleistocene, with the youngest fossils dated to 12,500 years in Central Europe.

Archaic humans have been interacting with lions since their arrival in Europe, and possibly even earlier.

The big cat held perceptible significance for Upper Paleolithic groups of Homo sapiens in Europe. This is well illustrated by the cave lion depictions in caves of south-eastern France, ivory sculptures including the famous Löwenmensch (Lion man) and figurines from the Swabian Jura’s deposits, and perforated cave lion canines worn as personal ornaments.

In the new research, University of Tübingen’s Dr. Gabriele Russo and colleagues analyzed an almost complete skeleton of a medium-sized cave lion from Siegsdorf, Germany, which were originally excavated in 1985 and date to 48,000 years ago.

The presence of cutmarks across bones including two ribs, some vertebrae, and the left femur previously suggested that ancient humans butchered the big cat after it had died.

However, the study authors found a partial puncture wound on the inside of the lion’s third rib, which appears to match the impact mark of a wooden-tipped spear.

The puncture is angled, suggesting the spear entered the left side of the lion’s abdomen and penetrated vital organs before impacting the third rib on the right side.

The characteristics of the puncture wound resemble those found on deer vertebrae which are known to have been made by Neanderthal spears.

The researchers suggest that the Siegsdorf specimen represents the earliest evidence of Neanderthals purposely hunting cave lions.

“The new evidence is the earliest instance of cave lion hunting with wooden spears,” they said.

“The continued use of wooden spears whilst Neanderthals were also likely using stone-tipped weaponry is evidenced at sites such as Neumark-Nord and Lehringen, and therefore their use at Siegsdorf is unsurprising.”

“The cutmarks on several bone elements of the Siegsdorf specimen suggest that the lion was processed at the kill site.”

“After the acquisition of meat and viscera, the carcass was abandoned.”

“The Siegsdorf Neanderthals likely killed a lion in poor condition and exploited the meat for consumption.”

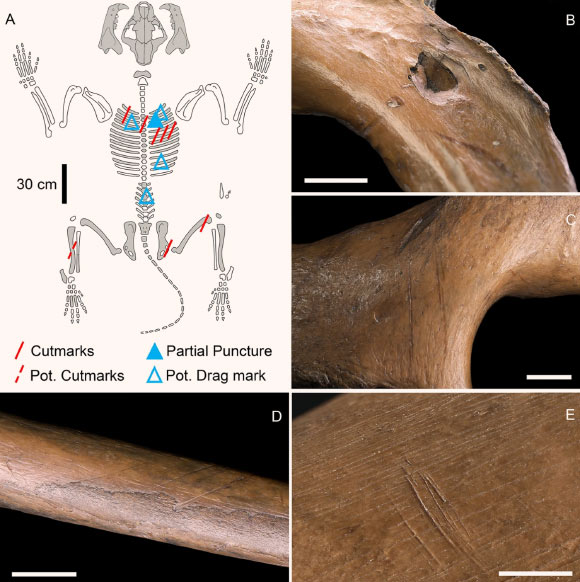

Anthropogenic modifications on the Siegsdorf lion skeleton: (A) Siegsdorf lion skeleton with distribution of observed anthropogenic modifications; elements highlighted in gray represent those that were originally unearthed; (B) rib III right ventral view with partial puncture; (C) right pubic bone with cutmarks; (D) rib VI right ventral view with cutmarks; (E) right distal femur caudal view with cutmarks. Scale bar – 1 cm. Image credit: Russo et al., doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-42764-0.

The scientists also analyzed phalange and sesamoid bones from the toes and lower limbs of three cave lion specimens from Einhornhöhle, Germany.

These bones also show cutmarks consistent with those generated when an animal is skinned.

The presence of the anthropogenically modified bones implies that they were left within the lion pelt, which was then abandoned at the site.

The location of these cutmarks suggests a careful approach was taken during the skinning process to ensure the claws remained preserved within the fur.

“This may constitute the earliest evidence of Neanderthals using a lion pelt, potentially for cultural purposes,” the authors said.

“Together, these findings provide new insights into the interactions between Neanderthals and cave lions in the Pleistocene.”

_____

G. Russo et al. 2023. First direct evidence of lion hunting and the early use of a lion pelt by Neanderthals. Sci Rep 13, 16405; doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-42764-0