The Basques are not direct descendants from hunter-gatherers of 10,000 years ago; instead, they have more recent genetic links to early Iberian farmers, according to a study of ancient DNA from eight people who lived in Europe 3,500 to 5,500 years ago.

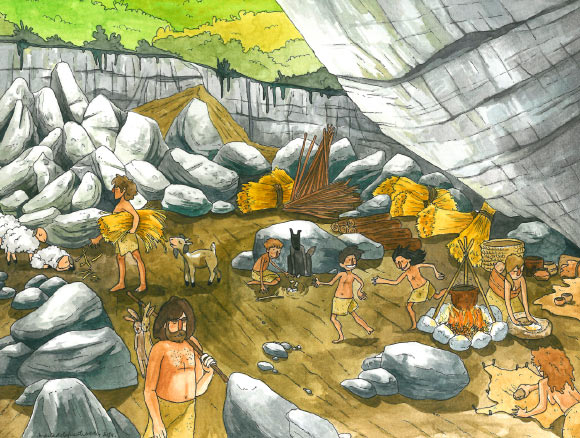

Illustration of every day life in the El Portalon cave during the Neolithic and Copper Age. Image credit: Maria de la Fuente.

The Mesolithic-Neolithic transition is an important period in the prehistory of Europe since it represents a major change in subsistence strategies, notably the change from small and mobile groups of hunter-gatherers to larger and sedentary farming populations. This transformation is arguably the basis of all complex sedentary societies and society as we know it today and it is often referred to as the Neolithic Revolution.

The origin and impact of agriculture in Europe has long been debated by archaeologists and has recently gained new insights from ancient DNA studies.

Scientists know that agricultural practices originated sometime approximately 11,000 years ago in the Middle East and the archaeological record shows that the ‘Neolithic package’ expanded into Europe and by 7,500 years ago, it had already reached most of Central Europe spreading later on into Scandinavia, the British Isles and along the Atlantic coast.

However, it has long been debated whether the spread of these cultural and technological practices was achieved by spreading the idea of farming or by farmers populating the areas, that is via cultural or demic diffusion.

Different studies have already demonstrated, through ancient DNA evidence, that hunter-gatherers and ancient farmers are two genetically different groups, arguing for a population replacement of resident hunter-gatherers and therefore supporting the demic diffusion hypothesis.

Some of these studies have also provided genomic evidence that Early Northern and Central European farmers are of southern origin.

In addition, more recent genomic studies have shown that hunter-gatherers and farmers must have interbred and that both groups contributed to the modern day European gene pool.

This time, scientists sequenced the DNA of early farmers found in the El Portalón cave at the world-famous site of Atapuerca in northern Spain.

“The El Portalon cave is a fantastic site with amazing preservation of artifact material,” said Dr Cristina Valdiosera of Uppsala University and La Trobe University, co-author on the study, published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Every year we find human and animal bones and artifacts, including stone tools, ceramics, bone artifacts and metal objects, it is like a detailed book of the last 10,000 years, providing a wonderful understanding of this period. The preservation of organic remains is great and this has enabled us to study the genetic material complementing the archaeology,” she said.

Dr Valdiosera and co-authors found that Iberian farmers are from the same group of people who migrated through the south of Europe and then populated Scandinavia and most of Europe.

“It was interesting to see that farmers in Iberia had interbred with local hunter-gatherers for thousands of years – but what was more surprising was that this mixing became greater through time,” Dr Valdiosera said. “It appears that the longer farming was practiced, the more mixing took place. Genetically people look increasingly like native hunter-gatherers and more distant from the original incoming farmers.”

The study also reports that the El Portalón individuals are genetically most similar to modern-day Basques.

“Our results show that the Basques trace their ancestry to early farming groups from Iberia, which contradicts previous views of them being a remnant population that trace their ancestry to Mesolithic hunter-gatherer groups,” said senior author Prof Mattias Jakobsson of Uppsala University.

“The difference between the Basques and other Iberian groups is these latter ones show distinct features of admixture from the East and from North Africa.”

“Basques have long been considered European outliers because of cultural differences,” said co-author Dr Colin Smith of La Trobe University.

“For example, their language is a complete isolate from the Indo-European languages and they show genetic distinctiveness from other Iberian populations.”

“It has even been suggested Basques are a modern extension of a local Paleolithic population from 10,000 years ago,” he added.

“But we now know that their closest ancestors are found in the Neolithic – and therefore are not that ancient.”

_____

Günther et al. Ancient genomes link early farmers from Atapuerca in Spain to modern-day Basques. PNAS, published online September 8, 2015; doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509851112