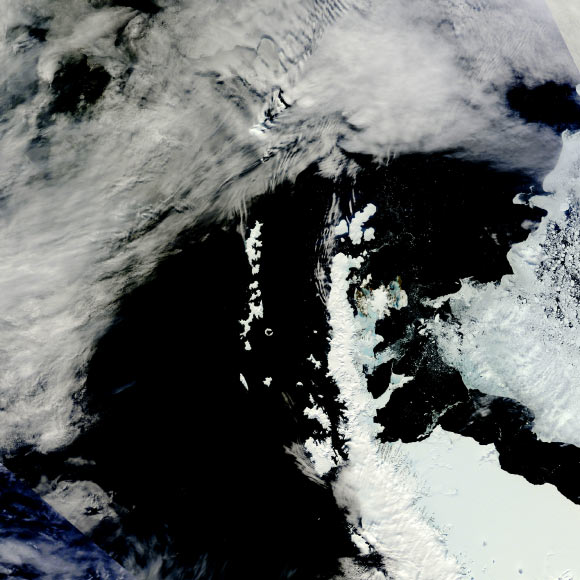

Using measurements of the elevation of the Antarctic ice sheet made by a suite of satellites, a group of scientists led by Dr Bert Wouters from the University of Bristol’s Glaciology Center found that the Southern Antarctic Peninsula showed no signs of change up to six years ago. Around 2009, multiple glaciers along a vast coastal expanse, measuring some 750 km in length, suddenly started to shed ice into the ocean at a nearly constant rate of 55 trillion liters of water each year. This makes the region the second largest contributor to sea level rise in Antarctica and the ice loss shows no sign of waning.

Nearly cloud-free view of the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula. Image credit: NASA / GSFC / MODIS Rapid Response Team.

The Southern Antarctic Peninsula is a region previously thought to be stable compared to other glacier masses in Antarctica.

Many glaciers in the region became destabilized in 2009, and they have been melting at accelerating rates ever since. These glaciers, which rest on bedrock that dips below sea level toward the continent’s interior, help to buttress inland ice shelves – but their structure is presumed to be unstable.

Now, Dr Wouters and co-authors have combined satellite altimetry and gravity observations from ESA’s CryoSat-2 and NASA’s GRACE satellites to show how such land-based ice has thinned over the past 12 years or so in the region.

Their results suggest that ice shelves on the Southern Antarctic Peninsula have weakened significantly, causing marine-terminating glaciers to flow faster into the sea.

“Between 2002 and 2010, the mass balance of such glaciers remained around zero,” Dr Wouters said.

But by about 2009, glaciers in the region had begun to lose mass at accelerating rates.

“To date, the glaciers added roughly 300 cubic km of water to the ocean. That’s the equivalent of the volume of nearly 350,000 Empire State Buildings combined,” said Dr Wouters, lead author of a paper about the results available online in the journal Science.

Today, these rapidly-melting glaciers pump out about 56 gigatons of water each year, constituting a major fraction of Antarctica’s contribution to rising sea level.

“The fact that so many glaciers in such a large region suddenly started to lose ice came as a surprise to us. It shows a very fast response of the ice sheet: in just a few years the dynamic regime completely shifted,” Dr Wouters said.

Based on their results, Dr Wouters and his colleagues from Utrecht University in Netherlands, the Alfred-Wegener-Institut Helmholtz-Zentrum für Polar- und Meeresforschung in Germany and the Laboratoire d’Etudes en Géophysique et Océanographie Spatiales in France, suggest that warming ocean currents are the likely culprit; changes in the wind circulation around Antarctica have increased the flow of warm subsurface waters from the deep ocean to the coastal zones, melting the ice shelves and glaciers from below.

_____

B. Wouters et al. 2015. Dynamic thinning of glaciers on the Southern Antarctic Peninsula. Science, vol. 348, no. 6237, pp. 899-903; doi: 10.1126/science.aaa5727