Geophysicists suggest that large chunks of an ancient tectonic plate known as the Farallon Plate are still present under parts of central California and Mexico.

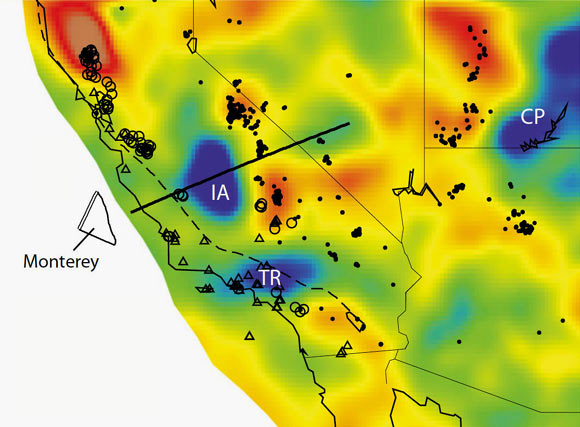

The Isabella anomaly, IA, is at the same depth as other fragments of the Farallon plate under Oregon and Washington (Forsyth lab / Brown University)

Around 100 million years ago, the Farallon oceanic plate lay between the converging Pacific and North American plates, which eventually came together to form the San Andreas fault. As those plates converged, much of the Farallon was subducted underneath North America and eventually sank deep into the mantle. Off the west coast of North America, the Farallon plate fragmented, leaving a few small remnants at the surface that stopped subducting and became part of the Pacific plate.

But a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests that large slabs from Farallon remain attached to these unsubducted fragments.

The geophysicists used seismic tomography and other data to show that part of the Baja region and part of central California near the Sierra Nevada mountains sit atop ‘fossil’ slabs of the Farallon plate.

“Many had assumed that these pieces would have broken off quite close to the surface,” said study co-author Dr Donald Forsyth of Brown University. “We’re suggesting that they actually broke off fairly deep, leaving these large slabs behind.”

Geologists had known for years about a ‘high velocity anomaly’ in seismic tomography data near the Sierra Nevada mountains in California. Seismic tomography measures the velocity of seismic waves deep underground. The speed of the waves provides information about the composition and temperature of the subsurface. Generally, slower waves mean softer and hotter material; faster waves mean stiffer and cooler material.

The anomaly in California, known as the Isabella anomaly, indicated that a large mass of relatively cool and dehydrated material is present at a depth of 60 to 125 miles below the surface. Just what that mass was wasn’t known, but there were a few theories. It was often explained by a process called delamination. The crust beneath the eastern part of the mountains is thin and the mantle hot, indicating that part of the lithospheric plate under the mountains had delaminated – broken off.

The anomaly might be the signature of that sunken hunk of lithosphere, which would be cooler and dryer than the surrounding mantle.

But a few years ago, scientists detected a new anomaly under the Mexico’s Baja Peninsula, due east of one of the known coastal remains of the Farallon plate. Because of its proximity to the Farallon fragment, the scientists thought it was very likely that the anomaly represented an underground extension of the fragment.

A closer look at the region showed that there are high-magnesium andesite deposits on the surface near the eastern edge of the anomaly. These kinds of deposits are volcanic rocks usually associated with the melting of oceanic crust material. Their presence suggests that the eastern edge of the anomaly represents the spots where Farallon finally gave way and broke off, sending andesites to the surface as the crust at the end of the subducted plate melted.

That led the team to suspect that perhaps the Isabella anomaly in California might also represent a slab still connected to an unsubducted fragment of the Farallon plate.

The study found that all of the anomalies are strongest at the same depth – right around 100 kilometers. And all of them line up nearly due east of known fragments from Farallon.

“The findings could force scientists to re-examine the tectonic history of western North America,” Dr Forsyth said. “In particular, it forces a rethinking of the delamination of the Sierra Nevada, which had been used to explain the Isabella anomaly.”

______

Bibliographic information: Yun Wang et al. Fossil slabs attached to unsubducted fragments of the Farallon plate. PNAS, published online before print March 18, 2013; doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214880110