The surface waters of the Arctic Ocean could reach levels of acidity that threaten the ability of animals to build and maintain their shells by 2030, according to a team of scientists led by Dr Jeremy Mathis of NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory.

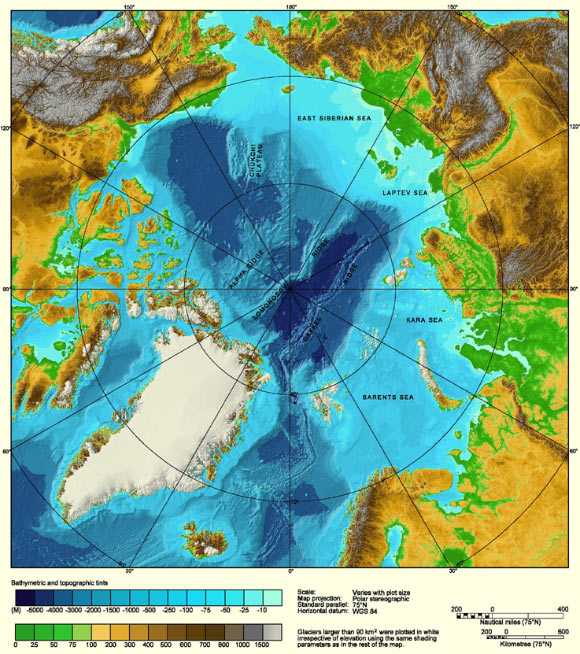

Bathymetric map of the Arctic Ocean.

A form of calcium carbonate in the ocean, called aragonite, is used by animals to construct and maintain shells.

When calcium and carbonate ion concentrations slip below tolerable levels, aragonite shells can begin to dissolve, particularly at early life stages.

As the water chemistry slips below the present-day range, which varies by season, shell-building organisms and the fish that depend on these species for food can be affected.

“The continental shelves of the Pacific-Arctic Region are especially vulnerable to the effects of ocean acidification because the intrusion of anthropogenic carbon dioxide is not the only process that can reduce pH and carbonate mineral saturation states for aragonite,” the scientists said.

“Enhanced sea ice melt, respiration of organic matter, upwelling, and riverine inputs have been shown to exacerbate carbon dioxide-driven ocean acidification in high-latitude regions. Additionally, the indirect effect of changing sea ice coverage is providing a positive feedback to ocean acidification as more open water will allow for greater uptake of atmospheric carbon dioxide.”

In their study, Dr Mathis and his colleagues collected observations on water temperature, salinity and dissolved carbon during two month-long expeditions to the Bering, Chukchi and Beaufort Seas onboard United States Coast Guard cutter Healy in 2011 and 2012.

These data were used to validate a predictive model for the region that calculates the change over time in the amount of calcium and carbonate ions dissolved in seawater.

The model suggests these levels will drop below the current range in 2025 for the Beaufort Sea, 2027 for the Chukchi Sea and 2044 for the Bering Sea.

“Our research shows that within 15 years, the chemistry of these waters may no longer be saturated with enough calcium carbonate for a number of animals from tiny sea snails to Alaska King crabs to construct and maintain their shells at certain times of the year,” explained Dr Mathis, who is the first author on the study published in the journal Oceanography.

“This change due to ocean acidification would not only affect shell-building animals but could ripple through the marine ecosystem.”

_____

Mathis, J.T. et al. 2015. Ocean acidification in the surface waters of the Pacific-Arctic boundary regions. Oceanography 28 (2): 122-135; doi: 10.5670/oceanog.2015.36