According to a new mice study reported in the Journal of Neuroscience, immune system cells called to the brain in response to stress lead to anxiety symptoms.

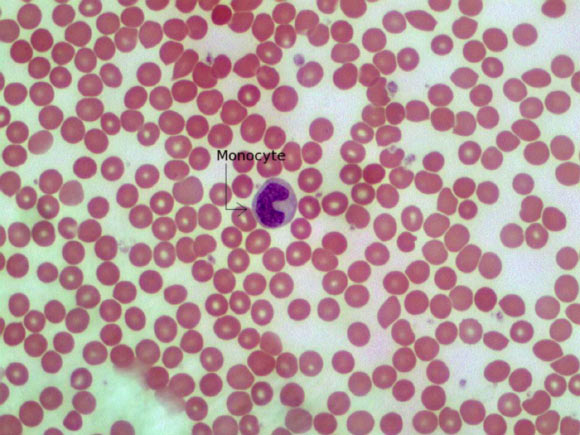

This image shows a monocyte – a type of white blood cell and part of the human body’s immune system (Adam Orlando / University of Massachusetts Amherst).

The study offers a new explanation of how stress can lead to mood disorders and identifies a subset of immune cells, called monocytes, that could be targeted by drugs for treatment of mood disorders. It also reveals new ways of thinking about the cellular mechanisms behind the effects of stress, identifying two-way communication from the central nervous system to the periphery – the rest of the body – and back to the central nervous system that ultimately influences behavior.

Unlike an infection, trauma or other problems that attract immune cells to the site of trouble in the body, this recruitment of monocytes that can promote inflammation doesn’t damage the brain’s tissue – but it does lead to symptoms of anxiety. The study showed that the brain under prolonged stress sends signals out to the bone marrow, calling up monocytes. The cells travel to specific regions of the brain and generate inflammation that causes anxiety-like behavior.

The mcie study showed that repeated stress exposure caused the highest concentration of monocytes migrating to the brain. The cells surrounded blood vessels and penetrated brain tissue in several areas linked to fear and anxiety, including the prefrontal cortex, amygdala and hippocampus, and their presence led to anxiety-like behavior in the mice.

Senior author Prof John Sheridan from the Ohio State’s Institute for Behavioral Medicine Research said: “in the absence of tissue damage, we have cells migrating to the brain in response to the region of the brain that is activated by the stressor. In this case, the cells are recruited to the brain by signals generated by the animal’s interpretation of social defeat as stressful.”

Mice were subjected to stress that might resemble a person in this study’s response to persistent life stressors. In this model of stress, male mice living together are given time to establish a hierarchy, and then an aggressive male is added to the group for two hours. This elicits a ‘fight or flight’ response in the resident mice as they are repeatedly defeated. The experience of social defeat leads to submissive behaviors and the development of anxiety-like behavior.

Mice subjected to zero, one, three or six cycles of this social defeat were then tested for anxiety symptoms. The more cycles of social defeat, the higher the anxiety symptoms; mice took longer to enter an open space and opted for darkness rather than light when given the choice. Anxiety symptoms corresponded to higher levels of monocytes that had traveled to the animals’ brains from the blood.

Additional experiments showed that these cells did not originate in the brain, but traveled there from the bone marrow.

“These findings do not apply to all forms of anxiety,” the scientists said, “but they are a game-changer in research on stress-related mood disorders.”

______

Bibliographic information: Eric S. Wohleb et al. 2013. Stress-Induced Recruitment of Bone Marrow-Derived Monocytes to the Brain Promotes Anxiety-Like Behavior. The Journal of Neuroscience, 33 (34): 13820-13833; doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1671-13.2013