An international team of paleobiologists has uncovered the fossil of a 105-million-year-old gymnosperm pollinating beetle, named Darwinylus marcosi. The fossil, encased in a piece of amber from Spain, is shedding new light on the various ways insects pollinated plants during the mid-Mesozoic era.

Reconstruction of Darwinylus marcosi on a gymnosperm host. Based on the pollen grains found in the amber with the beetle, paleobiologists believe that the beetle was closely associated with cycads, an ancient gymnosperm group of plants that have living relatives today throughout the warmer parts of the world. Image credit: Enrique Peñalver / Museo Geominero, Instituto Geológico y Minero de Espana.

“Darwinylus marcosi died in a sticky gob of tree sap some 105 million years ago in what is now Spain,” the researchers said.

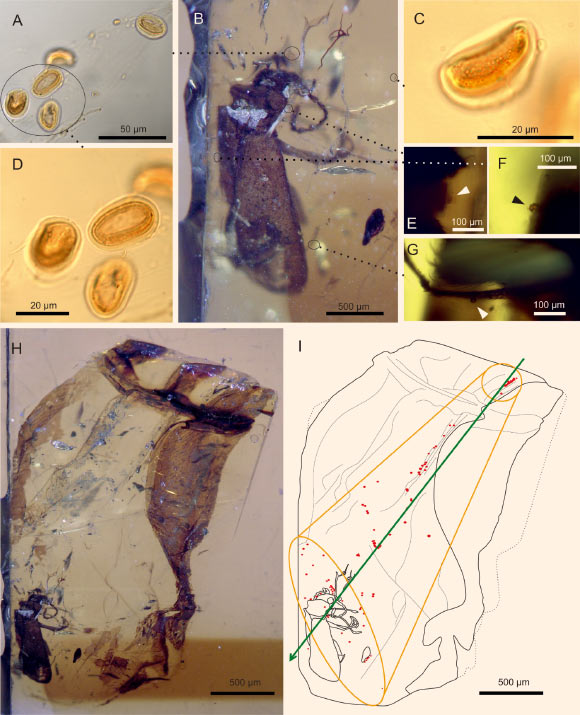

“As it thrashed about before drowning, more than 100 clumped pollen grains were dislodged from its body and released into the resin.”

“Five grains remained stuck to the beetle itself. Preserved with the beetle in the now-hard amber, the grains reveal that Darwinylus marcosi had been chewing a pollen meal with its jaw-like mouthparts just before it died.”

The amber dates to a time when flowering plants (angiosperms) were just beginning to appear and the Earth was overwhelmingly dominated by non-flowering plant species (gymnosperms), such as cycads, ginkgoaleans, bennettitaleans and conifers.

“Now, the discovery of Darwinylus marcosi in Spanish amber is proof of a new insect pollination mode that dates to the mid-Mesozoic: beetles with biting or jaw-like mouthparts and a chewing feeding style,” said Dr. Conrad Labandeira, a paleobiologist at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and lead co-author of a paper describing the new species in the journal Current Biology.

“This amber fossil is the first, direct evidence of a fourth major gymnosperm-insect pollination mode during this time.”

Darwinylus marcosi is the latest in a series of recently discovered gymnosperm-pollinating insects that flourished during the mid-Mesozoic.

Lacewings, scorpionflies, flies and moths with long, straw-like proboscises siphoned pollination drops.

Pollination drops are a liquid similar to the nectar of flowering plants that originate from deep funnel-like holes in pine-cone-like structures and other, often bizarre, gymnosperm ovule-bearing organs.

Flies (Diptera) with sponge-like mouthparts also lapped up this sweet plant nectar.

Thrips (Thysanoptera) with punch-and-suck mouthcone mouthparts drained the nutritious juices by cracking pollen grains, performing a different type of pollination.

All three of these insect-pollinator feeding modes have been found in 165- to 105-million-year-old amber and stone fossils that show gymnosperm pollen clinging to various mouthpart structures, heads and bodies of these insects.

“The newly reported discovery reveals the broad pattern of four distinctive pollinator modes that were present before the dominance of flowering plants between 125 and 90 million years ago,” Dr. Labandeira said.

“These pollinator modes survive to the present day, although the particular plant and insect participants are mostly long gone.”

Modern relatives of Darwinylus marcosi, the family Oedemeridae (false blister beetles), today pollinate flowering plants rather than gymnosperms.

“The amber fossil reveals that these beetles are one of a number of gymnosperm pollinators that successfully made the transition to feeding on and pollinating flowering plants,” Dr. Labandeira said.

This image (A) shows loose pollen grains from a gymnosperm plant, enlarged in (C) and (D), trapped in 105-million-year-old amber with Darwinylus marcosi. The beetle with the pollen in amber is featured in its entirety at (H). The photos (E), (F) and (G) show pollen grains from a gymnosperm plant that are stuck to the surface of the beetle. Based on their understanding of the fossilization process, scientists conjecture the resin covered the beetle in the direction of the green arrow and scattered the pollen grains loose from the beetle’s body into the adjacent resin within the cone-shaped envelope indicated in (I). Image credit: David Peris et al, doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.02.009.

“In the Cretaceous, many gymnosperms and the insects that pollinated them went extinct in a world-wide shake-up during the Aptian-Albian Gap between 125 to 90 million years ago.”

“This period is well-documented in the fossil record as gymnosperm diversity plunged and flowering plants soon came to dominate the Earth during a 35-million-year long transition.”

“Those insect pollinators that depended upon gymnosperms and couldn’t make the transition became extinct. The very few that remained with the gymnosperms and survived saw a major drop in their diversity.”

“Most gymnosperms today, such as conifers and the ginkgo, are wind pollinated; far fewer gymnosperms, such as the cycads and an unusual group known as gnetaleans, are insect-pollinated.”

_____

David Peris et al. False Blister Beetles and the Expansion of Gymnosperm-Insect Pollination Modes before Angiosperm Dominance. Current Biology, published online March 2, 2017; doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.02.009

This article is based on a press-release from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.