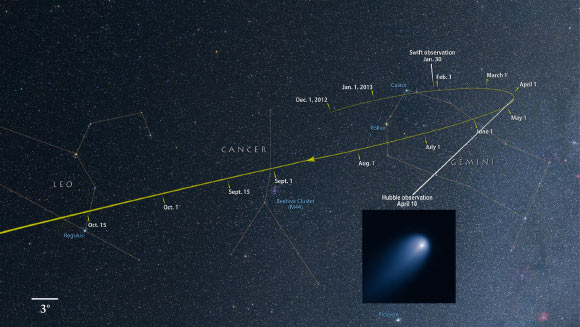

NASA scientists have released the clearest view yet of the comet ISON, a newly discovered sungrazing comet that may light up the sky later this year.

This image of the comet ISON was taken on April 10, 2013, when the comet was slightly closer than Jupiter’s orbit at a distance of 386 million miles from the Sun (NASA / ESA / J.-Y. Li, Planetary Science Institute / Hubble Comet ISON Imaging Science Team)

The comet ISON, also known as C/2012 S1, was discovered on September 21, 2012 by Vitali Nevski from Belarus and Artyom Novichonok from Russia.

“ISON is a clump of frozen gases mixed with dust, formed in a distant reach of the Solar System, traveling on an orbit influenced by the gravitational pull of the Sun and its planets. ISON’s orbit will bring it to a perihelion, or maximum approach to the Sun, of 700,000 miles on November 28, 2013,” said Dr Michael S. Kelley from the University of Maryland, a member of NASA’s team studying the comet.

ISON is potentially the ‘comet of the century’ because around the time the comet makes its closest approach to the Sun, it may briefly become brighter than the full Moon.

This contrast-enhanced image of the comet ISON reveals the subtle structure in the inner coma of the comet (NASA / ESA / J.-Y. Li, Planetary Science Institute / Hubble Comet ISON Imaging Science Team)

Right now the comet is far below naked-eye visibility, and so Hubble was used to snap the view of the approaching comet, which is presently hurtling toward the Sun at approximately 47,000 mph.

When the new image was taken on April 10, 2013 ISON was slightly closer than Jupiter’s orbit at a distance of 386 million miles from the Sun.

Next week while the Hubble still has ISON in view, the astronomers will use Hubble to gather information about ISON’s gases.

From December 2012 through October 2013, the comet ISON tracks through the constellations Gemini, Cancer, and Leo as it falls toward the Sun (NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center / Axel Mellinger)

“We want to look for the ratio of the three dominant ices, water, frozen carbon monoxide, and frozen carbon dioxide, or dry ice,” said Prof Michael A’Hearn, also from the University of Maryland.

“That can tell us the temperature at which the comet formed, and with that temperature, we can then say where in the Solar System it formed.”