An image from the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera on NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) reveals further details of the area where ESA’s ExoMars Schiaparelli test lander ended up following its descent on October 19, 2016.

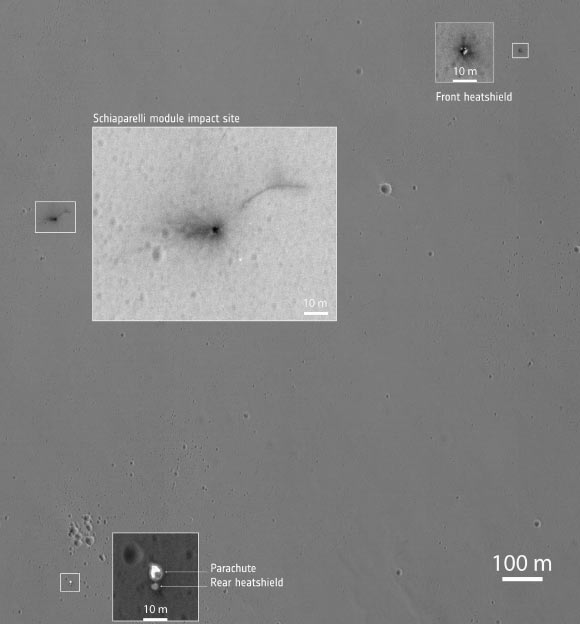

NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter imaged Schiaparelli’s landing site on October 25, 2016. The zoomed insets provide close-up views of what are thought to be several different hardware components associated with the lander’s descent to the Martian surface. These are interpreted as the front heatshield, the parachute and the rear heatshield to which the parachute is still attached, and the impact site of the module itself. The 100 m scale bar in the main image is only indicative. Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / University of Arizona.

The Schiaparelli lander, also known as Entry, descent, and landing Demonstrator Module (EDM), entered the Martian atmosphere at 2:42 p.m. GMT on October 19 for its 6-min descent to the surface.

According to mission controllers at the European Space Operations Centre, both the parachute and rear heatshield were ejected from Schiaparelli earlier than anticipated.

The module is thought to have fired its thrusters for only a few seconds before falling to the ground in Meridiani Planum from an altitude of 1.2-2.5 miles (2–4 km) and reaching the surface at more than 185 mph (300 km/h).

The first HiRISE image of the crash site provides close-ups of markings on the surface first found by MRO’s ‘context camera’ last week.

The image reveals three anomalous features within about 0.9 miles (1.5 km) of each other, as expected.

The main feature of the context images was a dark fuzzy patch of roughly 49 x 131 feet (15 x 40 m), associated with the impact of Schiaparelli itself.

The high-resolution images show a central dark spot, 8 feet (2.4 m) across, consistent with the crater made by a 300 kg object impacting at a few hundred mph.

The crater is predicted to be about 1.6 feet (0.5 m) deep and more detail may be visible in future images.

The asymmetric surrounding dark markings are more difficult to interpret. In the case of a meteoroid hitting the surface at 25,000-50,000 mph (40,000-80,000 km/h), debris surrounding a crater would typically point to a low incoming angle, with debris thrown out in the direction of travel.

But Schiaparelli was traveling considerably slower and, according to the normal timeline, should have been descending almost vertically after slowing down during its entry into the atmosphere from the west.

It is possible the hydrazine propellant tanks in the module exploded preferentially in one direction upon impact, throwing debris from the surface in the direction of the blast.

An additional long dark arc is seen to the upper right of the dark patch but is currently unexplained. It may also be linked to the impact and possible explosion.

Finally, there are a few white dots in the image close to the impact site, too small to be properly resolved in this image. These may or may not be related to the impact — they could just be ‘noise.’

Some 0.6 miles (0.9 km) south of Schiaparelli, a white feature seen in last week’s image is now revealed in more detail.

It is confirmed to be the 39-foot (12 m) diameter parachute used during the second stage of Schiaparelli’s descent, after the initial heatshield entry into the atmosphere. Still attached to it, as expected, is the rear heatshield, now clearly seen.

In addition to the Schiaparelli impact site and the parachute, a third feature has been confirmed as the front heatshield, which was ejected about 4 minutes into the 6-min descent, as planned.

The mottled bright and dark appearance of this feature is interpreted as reflections from the multilayered thermal insulation that covers the inside of the front heatshield.

The dark features around the front heatshield are likely from surface dust disturbed during impact.

_____

This article is based on a press-release from the European Space Agency.