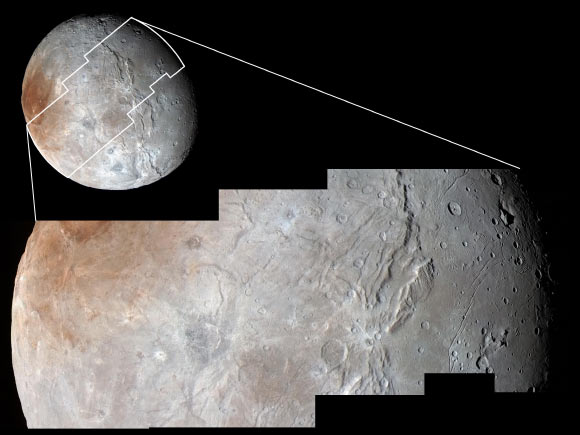

This high-resolution ‘extended color’ view of the Pluto-facing hemisphere of Charon – taken by New Horizons’ Ralph/Multispectral Visual Imaging Camera (MVIC) on July 14 and downlinked to Earth on September 21 – reveals details of a belt of fractures and canyons just north of the moon’s equator.

This impressive view of Charon was captured on July 14, 2015. Charon’s color palette is not as diverse as Pluto’s; most striking is the reddish north (top) polar region, informally named Mordor Macula. Image credit: NASA / Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory / Southwest Research Institute.

The view combines blue, red and infrared MVIC images and resolves details and colors on scales as small as 1.8 miles (2.9 km).

Charon’s great canyon system stretches more than 1,000 miles (1,600 km) across the entire face of the moon and likely around onto its far side. Four times as long as the Grand Canyon, and twice as deep in places, these faults and canyons indicate a titanic geological upheaval in Charon’s past.

“It looks like the entire crust of Charon has been split open. With respect to its size relative to Charon, this feature is much like the vast Valles Marineris canyon system on Mars,” said New Horizons team member Dr John Spencer of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

“We thought the probability of seeing such interesting features on this satellite of a world at the far edge of our Solar System was low, but I couldn’t be more delighted with what we see,” said Dr Ross Beyer of the SETI Institute and NASA Ames Research Center.

Charon’s cratered uplands at the left are broken by series of canyons, and replaced at the right by the rolling plains of Vulcan Planum. Image credit: NASA / Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory / Southwest Research Institute.

The scientists have also discovered that Vulcan Planum – the plains south of the Charon’s canyon – have fewer large craters than the regions to the north, indicating that they are noticeably younger.

The smoothness of the plains, as well as their grooves and faint ridges, are clear signs of wide-scale resurfacing. One possibility for the smooth surface is cryovolcanism.

“The team is discussing the possibility that an internal water ocean could have frozen long ago, and the resulting volume change could have led to Charon cracking open, allowing water-based lavas to reach the surface at that time,” said New Horizons team member Dr Paul Schenk of the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston.