After a journey of nine and a half years and three billion miles, NASA’s New Horizons is ready for a close look at the dwarf planet Pluto and its five moons.

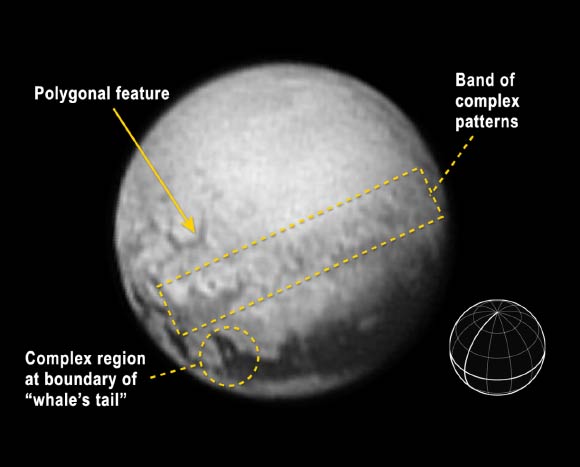

This image of Pluto reveals intriguing geologic details that are of keen interest to New Horizons team members. This image, taken early the morning of July 11, 2015, shows newly-resolved linear features above the equatorial region that intersect, suggestive of polygonal shapes. This image was captured when the spacecraft was 2.5 million miles (4 million km) from Pluto. Image credit: NASA / Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory / Southwest Research Institute.

New images are being gathered each day as New Horizons speeds closer to a July 14 flyby of the Pluto system.

“We’re close enough now that we’re just starting to see Pluto’s geology,” said Dr Curt Niebur of NASA Headquarters in Washington, a planetary scientist for the New Horizons mission.

A series of striking dark spots appears on the side of Pluto that always faces its largest moon, Charon – the face that will be invisible to New Horizons on July 14.

The spots are connected to a dark belt that circles Pluto’s equatorial region. What continues to pique the interest of New Horizons team members is their similar size and even spacing.

“It’s weird that they’re spaced so regularly,” Dr Niebur said.

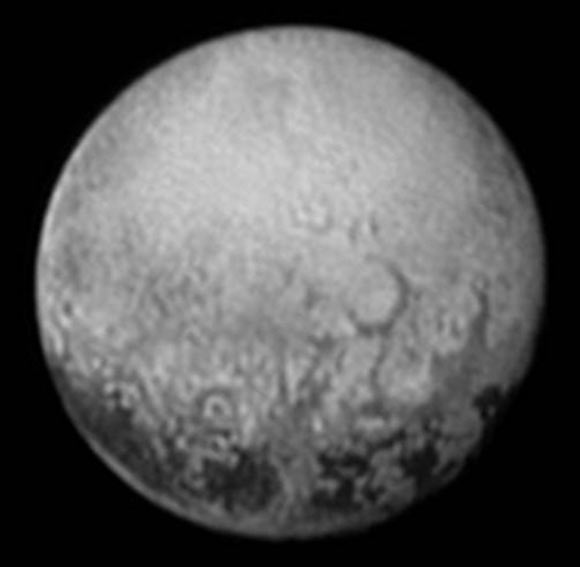

Tantalizing signs of geology on the dwarf planet Pluto are revealed in this image, taken on July 9, 2015 from 3.3 million miles (5.4 million km) away. Image credit: NASA / Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory / Southwest Research Institute.

“We can’t tell whether they’re plateaus or plains, or whether they’re brightness variations on a completely smooth surface,” added team member Dr Jeff Moore of NASA’s Ames Research Center.

The large dark areas are now estimated to be 300 miles (480 km) across, an area roughly the size of the state of Missouri. In comparison with earlier images, scientists now see that the dark areas are more complex than they initially appeared, while the boundaries between the dark and bright terrains are irregular and sharply defined.

In addition to solving the mystery of the spots, New Horizons scientists are interested in identifying other surface features such as impact craters, formed when smaller objects struck the dwarf planet.

“When we combine images like these of the far side with composition and color data the spacecraft has already acquired but not yet sent to Earth, we expect to be able to read the history of this face of Pluto,” Dr Moore said.

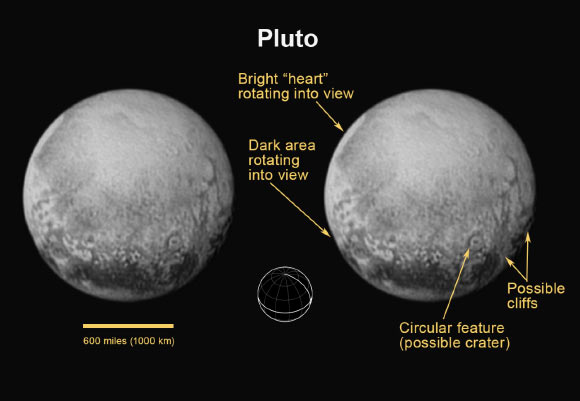

For the first time on Pluto, this view reveals linear features that may be cliffs, as well as a circular feature that could be an impact crater. Rotating into view is the bright heart-shaped feature that will be seen in more detail during New Horizons’ closest approach. This image was taken on July 11, 2015. Image credit: NASA / Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory / Southwest Research Institute.

At 7:49 a.m. EST (4:49 a.m. PST, 11:49 a.m. GMT, 1:49 p.m. CET, 5:19 p.m. IST, 9:49 p.m. AEST) on July 14, New Horizons will zip past Pluto at 30,800 miles per hour (49,600 km per hour), with a suite of seven science instruments busily gathering data.

The mission will complete the initial reconnaissance of the Solar System with the first-ever look at the icy dwarf planet.