Researchers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) are investigating the feasibility of creating a ‘windbot,’ a new kind of probe designed to stay aloft in an atmosphere of a gas giant for a long time.

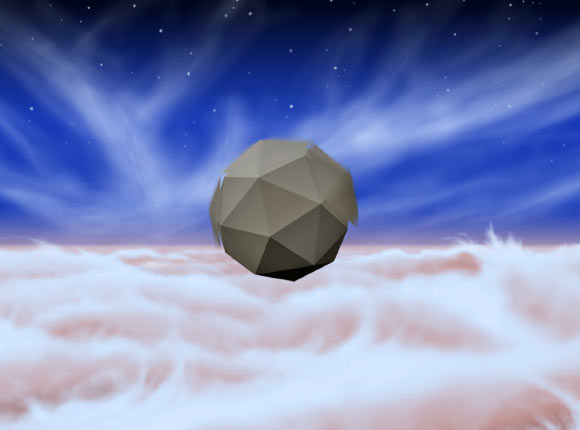

This artist’s concept shows a windbot bobbing through the skies of Jupiter, drawing energy from turbulent winds there; the windbot is portrayed as a polyhedron with sections that spin to absorb wind energy and create lift, although other potential configurations are being investigated. Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech.

Unlike terrestrial planets, gas giants like Jupiter and Saturn have no solid surface on which a probe to land on.

Two decades ago, in 1995, NASA’s Galileo spacecraft released a probe into the atmosphere of Jupiter that descended under a parachute. The probe survived about an hour before succumbing to high heat and pressure as it fell into the Jupiter’s ponderously deep atmosphere.

In contrast to the plummeting probe, a windbot could have rotors on several sides of its body that could spin independently to change direction or create lift.

“A dandelion seed is great at staying airborne. It rotates as it falls, creating lift, which allows it to stay afloat for long time, carried by the wind. We’ll be exploring this effect on windbot designs,” said Dr Adrian Stoica, principal investigator for the windbots study at NASA’s JPL.

The scientists think that, to stay airborne for a long time, a windbot would need to be able to use energy available in the gas giant’s atmosphere. That energy might not be solar, because the probe could find itself on the planet’s night side for a long time.

Nuclear power sources also could be a liability for a floating probe because of their weight. But winds, temperature variations and even a gas giant’s magnetic field could potentially be sources of energy an atmospheric probe could exploit.

As they begin their study, Dr Stoica and co-authors suspect the best bet for an atmospheric robot to harvest energy is turbulence – wind that’s frequently changing direction and intensity. The key is variability. High wind velocity isn’t enough. But in a dynamic, turbulent environment there are gradients that can be used.

The team is starting out by characterizing winds among the clouds of Jupiter to understand what kinds of places might be best for sending a windbot and to determine some of the technical requirements for its design.

“There are lots of things we don’t know. Does a windbot need to be 10 meters in diameter or 100? How much lift do we need from the winds in order to keep a windbot aloft,” Dr Stoica said.

One thing the scientists are pretty certain of is that a windbot would need to be able to sense the winds around itself in order to live off the turbulence.

To that end, the researchers plan to build a simple windbot model as part of their study. The aerodynamic modeling for this type of craft is particularly difficult, so they think having a physical model will be important.

Despite its potential, the windbot concept is not without its tradeoffs. The buoyant probe might have to sacrifice travel time in moving to interesting destinations on a planet to simply stay alive – trading a shorter route from point A to point B to follow the energy available from winds to stay aloft. At other times, when it has sufficient energy, it might be able to head to its destination via a more direct path.

The windbot concept is a long way from being ready to launch to Jupiter, but Dr Stoica and co-authors are excited to dive into their initial study.

“We don’t yet know if this idea is truly feasible. We’ll do the research to try and find out. But it pushes us to find other ways of approaching the problem, and that kind of thinking is extremely valuable,” Dr Stoica said.