An international team of archaeologists working in Bruniquel Cave in France has identified mysterious ring-like constructions that were built by early Neanderthals.

General view of the main Bruniquel Cave structure (structure A below) with superposed layers of aligned

Stalagmites. Image credit: E. Fabre, SSAC.

The ring-like structures are 176,500 years old and are made of whole and broken stalagmites (dubbed ‘speleofacts’), according to the team, led by Dr. Jacques Jaubert from the University of Bordeaux, Dr. Sophie Verheyden from the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences and Dr. Dominique Genty of the CNRS.

“Since its natural closing during the Pleistocene period and until its discovery in 1990, no humans entered Bruniquel Cave, located in the Tarn et Garonne region of southwestern France,” the archaeologists said.

“Near the entrance, the remains of large Pleistocene fauna and Holocene micro-fauna were found, and bears also left numerous traces of their presence: hibernation hollows, claw marks and a few footprints.”

“The most notable features, however, are the strange arrangement of two annular structures made of whole and broken stalagmites, accompanied by numerous traces of fire.”

The structures are located the largest chamber of Bruniquel Cave, about 1,100 feet (336 m) from the entrance.

“Other than these structures, signs of human activity are almost non-existent and uncertain,” the scientists said.

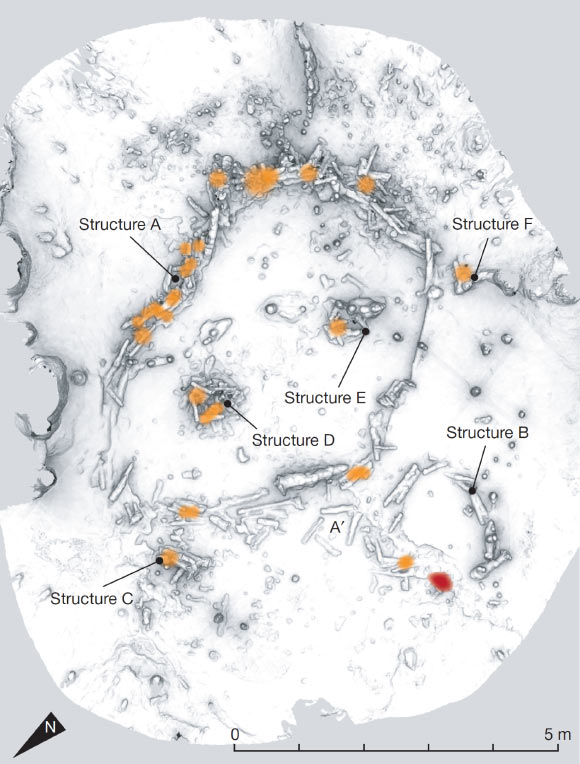

They identified two categories of structures in the cave: two ring-like ones, which are the most impressive, and four smaller stalagmite accumulation structures.

The largest ring-like structure is 22 x 14.8 feet (6.7 x 4.5 m), and the smaller one is 7.2 x 6.9 feet (2.2 x 2.1 m).

Bruniquel Cave structures: the six structures are composed only of stalagmites or fragments of stalagmites, aligned and superimposed (A, B) or accumulated (C, D, E, F); the orange spots represent the heated zones, all located on the construction elements; the red spot (structure B) represents a char concentration (mainly burnt bone fragments) on the ground. Image credit: Jacques Jaubert et al.

“The annular structures are composed of one to four superposed layers of aligned stalagmites,” the archaeologists said.

“Notably, some short elements were placed inside the superposed layers to support them. Other stalagmites were placed vertically against the main structure in the manner of stays, perhaps to reinforce the constructions.”

“The accumulation structures consist of stacks of stalagmites and are from 1.8 to 8.5 feet (0.55 – 2.6 m) in diameter. Two of them are located in the centre of the larger annular construction, while the other two are outside of it.”

Overall, about 400 pieces were used, comprising a total length of 369 feet (112.4 m) and an average weight of 2.2 tons of calcite.

“Neanderthals made these structures by breaking stalagmites and rearranging the pieces. After the site was abandoned, new layers of calcite, including new stalagmite growth, formed on the man-made structures.”

According to the team, traces of fire are present on all six structures. They consist of 57 reddened, more or less fissured ‘speleofacts,’ and 66 blackened ones.

“The red and black colors are clearly not related to precipitates from the dripping water since no similar traces are observed on the ceiling,” the researchers said.

By dating the end of the growth of the stalagmites used in the structures and the beginning of the regrowth sealing those same structures, the team has estimated the age of the installation at 176,500 years.

Additional samples, in particular of the calcite covering a burnt bone, confirmed this surprising result.

“We now know that, some 140 millennia before the arrival of modern man, Europe’s first Neanderthals were occupying deep caves, building complex structures and maintaining fires in them,” the scientists said.

“The attribution of the Bruniquel constructions to early Neanderthals is unprecedented in two ways,” they said.

“First, it reveals the appropriation of a deep karst space (including lighting) by a pre-modern human species. Second, it concerns elaborate constructions that have never been reported before, made with hundreds of partially calibrated, broken stalagmites.”

“Eliminating the unlikely hypothesis of shelter, given the structures’ distance from the entrance, was it to find materials of now-unknown utility? Could it have been for ‘technical’ purposes, such as water storage? Or for the observance of religious or other rites?”

In any case, the scientists confirm that early Neanderthals had to have an advanced social organization to build such constructions.

“Further studies will attempt to explain their function, which for the moment remains the biggest mystery surrounding Bruniquel Cave,” they said.

The team’s findings were published online this week in the journal Nature.

_____

Jacques Jaubert et al. Early Neanderthal constructions deep in Bruniquel Cave in southwestern France. Nature, published online May 25, 2016; doi: 10.1038/nature18291