Historians have long debated whether the first major phase of compilation of Biblical texts took place before or after the destruction of Jerusalem and the Kingdom of Judah in 586 BC. While they agree that key texts were written starting in the 7th century BC, the exact date of the compilation remains in question.

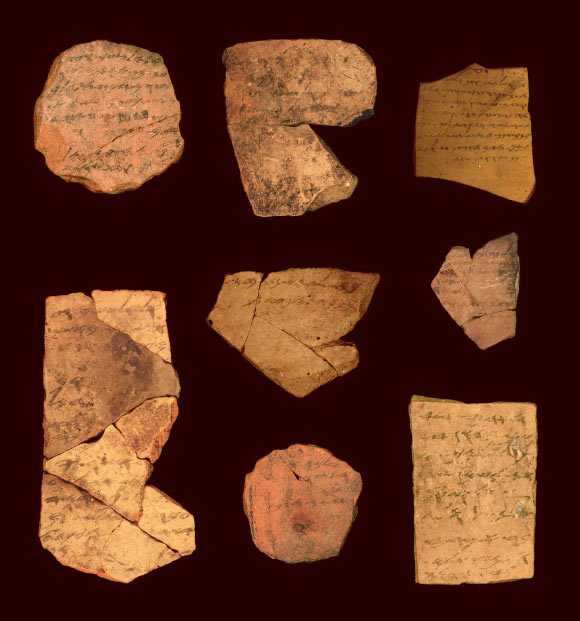

Ink inscriptions on clay (ostraca) from Arad. These documents are dated to the latest phase of the First Temple Period in Judah, around 600 BC. Image credit: Michael Cordonsky / Tel Aviv University / Israel Antiquities Authority.

A new interdisciplinary study, led by Dr. Shira Faigenbaum-Golovin of Tel Aviv University, Israel, suggests that widespread literacy was required for this massive undertaking and provides empirical evidence of that literacy in the final days of the Kingdom of Judah.

Using cutting-edge computerized image processing and machine learning tools, Dr. Faigenbaum-Golovin and her colleagues at Tel Aviv University analyzed 16 ink inscriptions found in the desert fortress of Arad.

The scientists deduced that the texts had been written by at least six authors.

“We report our investigation of 16 inscriptions from the Judahite desert fortress of Arad, dated to around 600 BC — the eve of Nebuchadnezzar’s destruction of Jerusalem,” they wrote in a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences this week.

“The inquiry is based on new methods for image processing and document analysis, as well as machine learning algorithms. These techniques enable identification of the minimal number of authors in a given group of inscriptions.”

“Our algorithmic analysis, complemented by the textual information, reveals a minimum of six authors within the examined inscriptions.”

The content of the inscriptions disclosed that reading and writing abilities existed throughout the military chain of command, from the highest echelon all the way down to the deputy quartermaster of the fort.

The inscriptions consisted of instructions for troop movements and the registration of expenses for food.

The tone and nature of the commands precluded the role of professional scribes.

Considering the remoteness of Arad, the small garrison stationed there, and the narrow time period of the inscriptions, this finding indicates a high literacy rate within Judah’s administrative apparatus — and provides a suitable background for the composition of a critical mass of Biblical texts.

“We found indirect evidence of the existence of an educational infrastructure, which could have enabled the composition of Biblical texts,” said Prof. Eliezer Piasetzky, co-author on the study.

“Literacy existed at all levels of the administrative, military and priestly systems of Judah. Reading and writing were not limited to tiny elite.”

“Now our job is to extrapolate from Arad to a broader area,” said senior author Prof. Israel Finkelstein. “Adding what we know about Arad to other forts and administrative localities across ancient Judah, we can estimate that many people could read and write during the last phase of the First Temple period. We assume that in a kingdom of some 100,000 people, at least several hundred were literate.”

“Following the fall of Judah, there was a large gap in production of Hebrew inscriptions until the second century BCE, the next period with evidence for widespread literacy,” he said.

“This reduces the odds for a compilation of substantial Biblical literature in Jerusalem between ca. 586 and 200 BC.”

_____

Shira Faigenbaum-Golovin et al. Algorithmic handwriting analysis of Judah’s military correspondence sheds light on composition of Biblical texts. PNAS, published online April 11, 2016; doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522200113