ESA’s Gaia mission has released the largest catalogue ever of Milky Way stars. It includes the positions on the sky for approximately 1.7 billion stars, as well as a measure of their overall brightness at optical wavelengths. Preliminary analysis of this phenomenal data reveals fine details about the make-up of the Milky Way’s stellar population and about how stars move, essential information for investigating the formation and evolution of our Galaxy.

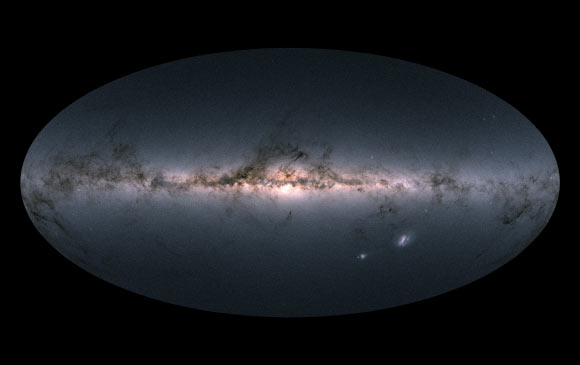

Gaia’s all-sky view of our Milky Way Galaxy and neighboring galaxies, based on measurements of nearly 1.7 billion stars. Brighter regions indicate denser concentrations of especially bright stars, while darker regions correspond to patches of the sky where fewer bright stars are observed. The color representation is obtained by combining the total amount of light with the amount of blue and red light recorded by Gaia in each patch of the sky. The bright horizontal structure that dominates the image is the Galactic plane, the flattened disc that hosts most of the stars in our home Galaxy. In the middle of the image, the Galactic center appears vivid and teeming with stars. Darker regions across the Galactic plane correspond to foreground clouds of interstellar gas and dust, which absorb the light of stars located further away, behind the clouds. Many of these conceal stellar nurseries where new generations of stars are being born. Sprinkled across the image are also many globular and open clusters — groupings of stars held together by their mutual gravity, as well as entire galaxies beyond our own. The two bright objects in the lower right of the image are the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, two dwarf galaxies orbiting the Milky Way. In small areas of the image where no color information was available — to the lower left of the Galactic center, to the upper left of the Small Magellanic Cloud, and in the top portion of the map — an equivalent grayscale value was assigned. Image credit: ESA / Gaia / DPAC.

Launched on December 19, 2013, the Gaia satellite both rotates and orbits around the Earth, while surveying the sky with its two telescopes.

Equipped with 106 CCDs forming the equivalent of a camera with a resolution of a billion pixels, it surveys 50 million stars per day, each time carrying out ten measurements, which represents a total of 500 million data points per day.

Gaia’s first data release, based on just over one year of observations, was published on September 14, 2016. It was based on observations taken by the satellite between July 25, 2014 and September 16, 2015. It included the position and brightness for 1.1 billion stars, but distances and motions for just the brightest two million stars.

The second data release, which covers the period between July 25, 2014 and May 23, 2016, pins down the positions of nearly 1.7 billion stars, and with a much greater precision.

For some of the brightest stars in the survey, the level of precision equates to Earth-bound observers being able to spot a Euro coin lying on the surface of the Moon.

With these accurate measurements it is possible to separate the parallax of stars — an apparent shift on the sky caused by Earth’s yearly orbit around the Sun – from their true movements through the Milky Way.

The new catalogue lists the parallax and velocity across the sky, or proper motion, for more than 1.3 billion stars. From the most accurate parallax measurements, about 10% of the total, astronomers can directly estimate distances to individual stars.

“The observations collected by Gaia are redefining the foundations of astronomy,” said Dr. Günther Hasinger, ESA Director of Science.

“Gaia is an ambitious mission that relies on a huge human collaboration to make sense of a large volume of highly complex data. It demonstrates the need for long-term projects to guarantee progress in space science and technology and to implement even more daring scientific missions of the coming decades.”

“The second Gaia data release represents a huge leap forward with respect to ESA’s Hipparcos satellite, Gaia’s predecessor and the first space mission for astrometry, which surveyed some 118,000 stars almost thirty years ago,” added Dr. Anthony Brown, of Leiden University in the Netherlands.

“The sheer number of stars alone, with their positions and motions, would make Gaia’s new catalogue already quite astonishing. But there is more: this unique scientific catalogue includes many other data types, with information about the properties of the stars and other celestial objects, making this release truly exceptional.”

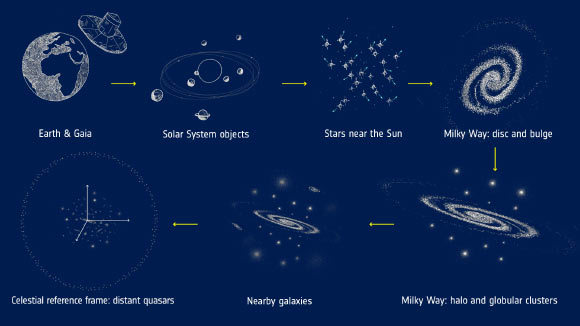

Gaia’s second data release contains a high-precision catalogue of the entire sky, covering celestial objects near and far. It includes objects such as asteroids in our Solar System as well as the stellar population of our Milky Way Galaxy and its satellites — globular clusters and nearby galaxies. It also extends to distant quasars that are being used to define a new celestial reference system. This infographic summarizes the cosmic scales covered by this comprehensive dataset, which provides a wide range of topics for the astronomy community. Image credit: ESA.

The comprehensive dataset provides a wide range of topics for the astronomy community.

As well as positions, the data include brightness information of all surveyed stars and color measurements of nearly all, plus information on how the brightness and color of half a million variable stars change over time. It also contains the velocities along the line of sight of a subset of seven million stars, the surface temperatures of about a hundred million and the effect of interstellar dust on 87 million.

Gaia also observes objects in our Solar System: the second data release comprises the positions of more than 14,000 known asteroids, which allows precise determination of their orbits.

Further afield, the satellite closed in on the positions of half a million distant quasars, bright galaxies powered by the activity of the supermassive black holes at their cores.

These sources are used to define a reference frame for the celestial coordinates of all objects in the Gaia catalogue, something that is routinely done in radio waves but now for the first time is also available at optical wavelengths.

“Gaia is astronomy at its finest,” said Dr. Fred Jansen, Gaia mission manager at ESA.

“Scientists will be busy with this data for many years, and we are ready to be surprised by the avalanche of discoveries that will unlock the secrets of our Galaxy.”

A series of papers describing the data contained in Gaia’s second data release and their validation process appears in a special issue of the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.