A University of Oxford-led team of scientists has observed bearded capuchins (Sapajus libidinosus) in Brazil deliberately break stones, unintentionally producing sharp-edged flakes that have the characteristics and morphology of intentionally produced hominin tools.

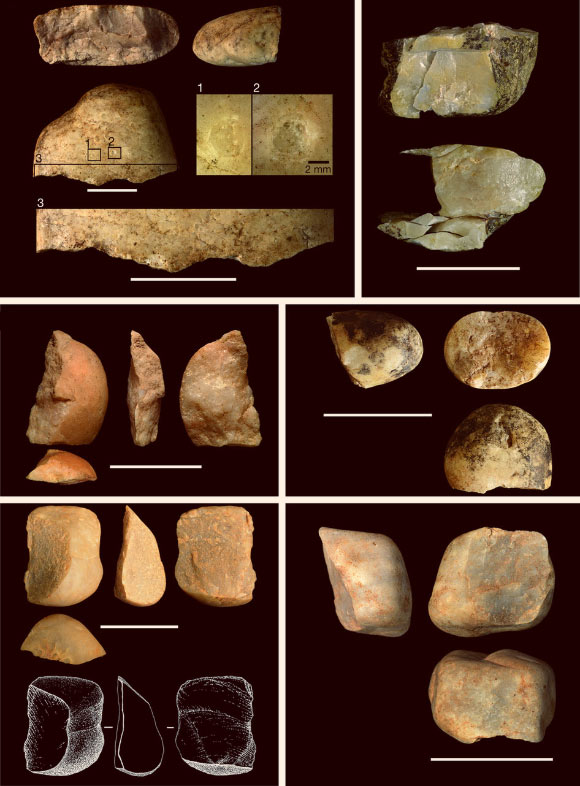

Examples of flaked stones produced by bearded capuchins (Sapajus libidinosus). Scale bars – 5 cm. Image credit: Tomos Proffitt et al.

“Our understanding of the new technologies adopted by our early ancestors helps shape our view of human evolution,” said lead co-author Dr. Michael Haslam, from the Primate Archaeology Research Group at the University of Oxford, UK.

“The emergence of sharp-edged stone tools that were fashioned and hammered to create a cutting tool was a big part of that story.”

“The fact that we have discovered monkeys can produce the same result does throw a bit of a spanner in the works in our thinking on evolutionary behavior and how we attribute such artifacts,” he added.

“While humans are not unique in making this technology, the manner in which they used them is still very different to what the monkeys seem capable of.”

Dr. Haslam and his colleagues from the University College London and the Universities of São Paulo and Oxford observed the bearded capuchins in Serra da Capivara National Park in northeast Brazil unintentionally creating fractured flakes and cores.

While hominins made stone flake tools for cutting and butchery tasks, the researchers admit that it is unclear why the monkeys perform this behavior.

The capuchins are seen licking them, so the team suggests that the monkeys may be trying to extract powdered silicon — known to be an essential trace nutrient — or to remove lichen for some as yet unknown medicinal purpose.

“At no point did the monkeys try to cut or scrape using the flakes,” the scientists said.

The capuchins were observed engaging in ‘stone on stone percussion,’ whereby they individually selected rounded quartzite cobbles and then using one or two hands struck the ‘hammer stone’ forcefully and repeatedly on quartzite cobbles embedded in a cliff face.

This action crushed the surface and dislodged cobbled stones, and the hand-held hammer stones became unintentionally fractured, leaving an identifiable primate archaeological record.

As well as using the active hammer-stone to crush ‘passive hammers’ (stones embedded in the outcrop), the monkeys were also observed re-using broken hammer-stones as ‘fresh’ hammers.

Dr. Haslam and co-authors examined more than 100 fragmented stones collected from the ground immediately after the capuchins had dropped them, as well as from the surface and excavated areas in the site.

They gathered complete and broken hammer-stones, complete and fragmented flakes and passive hammers.

Around half of the fractured flakes exhibited conchoidal fracture, which is typically associated with the hominin production of flakes.

“Within the last decade, studies have shown that the use and intentional production of sharp-edged flakes are not necessarily linked to early humans who are our direct relatives, but instead were used and produced by a wider range of hominins,” said study lead author Dr. Tomos Proffitt, from the School of Archaeology at the University of Oxford.

“However, this study goes one step further in showing that modern primates can produce archaeologically identifiable flakes and cores with features that we thought were unique to hominins.”

“This does not mean that the earliest archaeological material in East Africa was not made by hominins.”

“It does, however, raise interesting questions about the possible ways this stone tool technology developed before the earliest examples in the archaeological record appeared. It also tells us what this stone tool technology might look like.”

The findings were published online this week in the journal Nature.

_____

Tomos Proffitt et al. Wild monkeys flake stone tools. Nature, published online October 19, 2016; doi: 10.1038/nature20112