A team of researchers from the University of Oxford has identified four regions of the human genome associated with left-handedness in the general population and linked their effects with brain architecture.

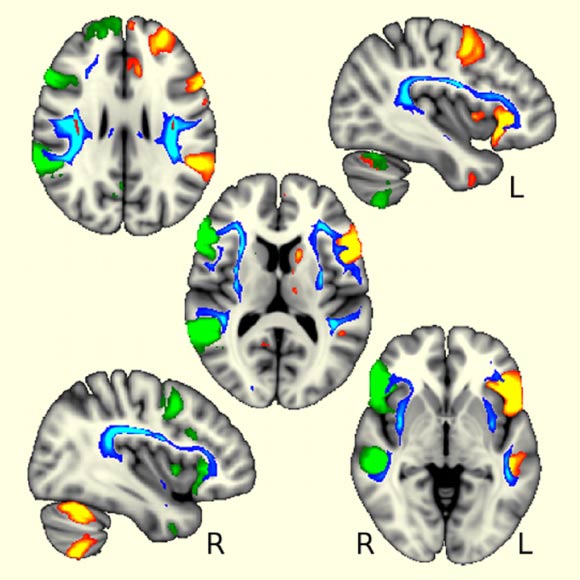

The language brain regions were more coordinated in left-handers between the two sides of the brain (in green and orange) and were also connected by the white matter tracts influenced by one genetic region related to handedness (in blue). Image credit: Gwenaëlle Douaud, University of Oxford.

“Throughout history, left-handedness has been considered unlucky, or even malicious,” said University of Oxford’s Professor Dominic Furniss.

“Indeed, this is reflected in the words for left and right in many languages. For example, in English ‘right’ also means correct or proper; in French ‘gauche’ means both left and clumsy.”

“Here we’ve demonstrated that left-handedness is a consequence of the developmental biology of the brain, in part driven by the complex interplay of many genes. It is part of the rich tapestry of what makes us human.”

Professor Furniss and colleagues identified the genetic variants associated with left-handedness by analyzing the genomes of about 400,000 people from UK Biobank, which included 38,332 left-handers.

Of the four genetic regions the team identified (rs199512, rs45608532, rs13017199, and rs3094128), three of these were associated with proteins involved in brain development and structure.

In particular, these proteins were related to microtubules, which are part of the scaffolding inside cells, called the cytoskeleton, which guides the construction and functioning of the cells in the body.

Using detailed brain imaging from approximately 10,000 of these participants, the scientists found that these genetic effects were associated with differences in brain structure in white matter tracts, which contain the cytoskeleton of the brain that joins language-related regions.

“We discovered that, in left-handed participants, the language areas of the left and right sides of the brain communicate with each other in a more coordinated way,” said University of Oxford’s Dr. Akira Wiberg.

“This raises the intriguing possibility for future research that left-handers might have an advantage when it comes to performing verbal tasks, but it must be remembered that these differences were only seen as averages over very large numbers of people and not all left-handers will be similar.”

“Many animals show left-right asymmetry in their development, such as snail shells coiling to the left or right, and this is driven by genes for cell scaffolding, what we call the cytoskeleton,” said University of Oxford’s Professor Gwenaëlle Douaud.

“For the first time in humans, we have been able to establish that these handedness-associated cytoskeletal differences are actually visible in the brain.”

“We know from other animals, such as snails and frogs, that these effects are caused by very early genetically-guided events, so this raises the tantalizing possibility that the hallmarks of the future development of handedness start appearing in the brain in the womb.”

The authors also found correlations between the genetic regions involved in left-handedness and a very slightly lower chance of having Parkinson’s disease, but a very slightly higher chance of having schizophrenia.

However, they stressed that these links only correspond to a very small difference in the actual number of people with these diseases, and are correlational so they do not show cause-and-effect.

“Studying the genetic links could help to improve understanding of how these serious medical conditions develop,” they said.

The study was published in the journal Brain.

_____

Akira Wiberg et al. Handedness, language areas and neuropsychiatric diseases: insights from brain imaging and genetics. Brain, published online September 5, 2019; doi: 10.1093/brain/awz257