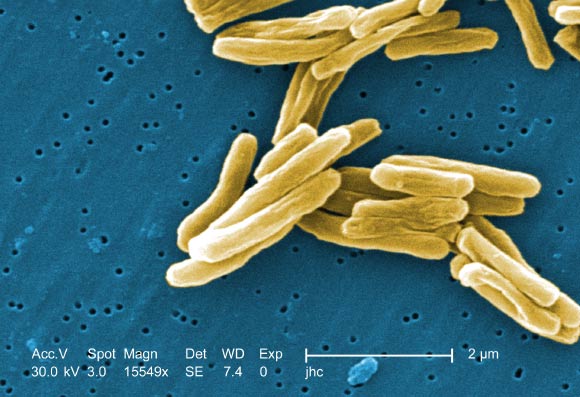

A research team led by Rockefeller University scientists has discovered a genetic variant that makes people more vulnerable to tuberculosis, a disease caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The team also uncovered genetic mutations that rob the immune system of its ability to combat more ubiquitous germs of the same bacterial family, mycobacteria. The researchers reported their results in two papers published December 21, 2018 in the journal Science Immunology.

About a quarter of the world’s population is infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, but this bacterium causes tuberculosis in less than 10% of infected individuals, generally within two years of infection (a situation referred to here as primary tuberculosis).

In the countries in which tuberculosis is highly endemic, primary tuberculosis is particularly common in children, who often develop life-threatening disease.

Hoping to better understand why only some people are prone to tuberculosis, Rockefeller University’s Professor Jean-Laurent Casanova and colleagues collected and analyzed DNA samples from patients with active forms of the disease.

They discovered that the risk of developing tuberculosis is heightened in people who have two copies of a particular variation to the gene coding for the enzyme TYK2. Moreover, they found that this genetic condition is fairly widespread.

“In Europeans, one in 600 people have two copies of this TYK2 variation. And in the rest of the population the rate is between one in 1,000 to one in 10,000 — which is still not rare,” Professor Casanova said.

Historically, a person with a TKY2 mutation would be unaware of her susceptibility until it was too late. However, now that the researchers have identified this risk factor, individuals travelling to regions where tuberculosis is common can obtain genetic tests to find out whether they are vulnerable to the disease.

“Most of mycobacteria are poorly virulent — they’re weak, compared to Mycobacterium tuberculosis — so in the vast majority of people, they’ll never cause disease,” Professor Casanova said.

“In a small fraction of the population, however, these common microbes can lead to serious infections — a condition known as Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease (MSMD).”

Recently, Professor Casanova and co-authors identified two novel genetic causes of this condition, one that leads to a deficiency of the receptor for the immune cell protein interleukin 23 (IL-23), and one that leads to a deficiency of the receptor for a similar protein, interleukin 12 (IL-12).

Both IL-12 and IL-23 promote production of gamma interferon, a molecule that contributes to immunity against mycobacterial infections.

When cells fail to produce this interferon at normal levels, they become susceptible to widespread, poorly virulent mycobacteria. In other words, they develop MSMD.

The risk for this condition is highest, the scientists found, among individuals with a mutation that affects both IL-12 and IL-23 receptors.

“Though the two proteins are individually important, their function is somewhat redundant. So most people missing only IL-12 or IL-23 will be ok, only some of them developing MSMD,” Professor Casanova said.

“But if you lack both, then you have very low interferon production and will almost certainly develop the condition.”

The researchers also looked into why a TYK2 mutation might make people prone to tuberculosis.

They found that when the enzyme’s function is disturbed, cells don’t respond normally to IL-23, and therefore produce less gamma interferon.

And though low interferon levels may suffice to stave off poorly-virulent bacteria, they do not protect against stronger microbes like Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

“This finding suggests a new strategy for treating people with tuberculosis,” Professor Casanova said.

“What IL-23 does for a living is induce gamma interferon, which, it turns out, you can buy at the pharmacy. So if you’re prone to tuberculosis because of a mutation to TYK2, you could potentially prevent or treat it with that kind of medicine.”

_____