A high-resolution trace-element analysis of 2.6-2.1-million-year-old teeth from an extinct hominin called Australopithecus africanus has revealed that infants were breastfed continuously from birth to about one year of age; nursing appears to continue in a cyclical pattern in the early years for Australopithecus infants; seasonal changes and food shortages caused mothers to supplement gathered foods with breast milk.

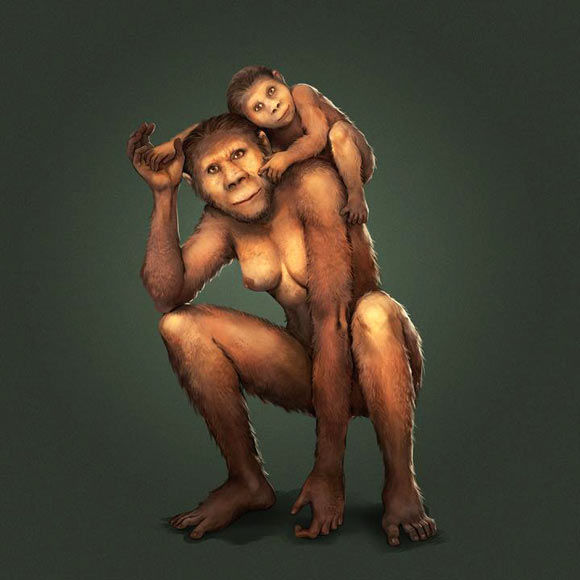

Australopithecus africanus, a mother with an infant. Image credit: Jose Garcia & Renaud Joannes-Boyau, Southern Cross University.

Breastfeeding is a critical aspect of human development, and the duration of exclusive nursing and the timing of introducing solid food to the diet are also important determinants of health in human and other primate populations.

Many aspects of nursing, however, remain poorly understood.

“Seeing how breastfeeding has evolved over time can inform best practices for modern humans by bringing in evolutionary medicine,” said Dr. Christine Austin, a scientist at the Icahn School of Medicine in New York.

Dr. Austin and colleagues developed a method to analyze trace minerals in ancient teeth.

“Like trees, teeth contain growth rings that can be counted to estimate age. Teeth rings also incorporate dietary minerals as they grow,” they explained.

“Breast milk contains barium, which accumulates steadily in an infant’s teeth and then drops off after weaning.”

In the study, the researchers examined two sets of fossilized teeth of Australopithecus africanus from the Sterkfontein Cave outside Johannesburg, South Africa.

They found patterns of barium accumulation, suggesting that infants of this species likely breast fed for about a year, an interval which may have helped them overcome seasonal food shortages.

The species resided in savannahs with wet summers, when food was likely abundant, and dry winters, when food was scarce.

Cyclical accumulations of lithium in the specimens’ teeth suggest Australopithecus africanus endured food scarcity during the dry season, which may have contributed to its eventual extinction.

“Our results show this species is a little closer to humans than the other great apes which have such different nursing behaviors,” Dr. Austin said.

“We gained new insight into the way our ancestors raised their young, and how mothers had to supplement solid food intake with breast milk when resources were scarce,” said Dr. Joannes-Boyau, a geochemist at Southern Cross University.

“These finds suggest for the first time the existence of a long-lasting mother-infant bond in Australopithecus africanus. This makes us to rethink on the social organizations among our earliest ancestors,” added Dr. Luca Fiorenza, an expert in the evolution of human diet at Monash University.

“Fundamentally, our discovery of a reliance by Australopithecus africanus mothers to provide nutritional supplementation for their offspring and use of fallback resources highlights the survival challenges that populations of early human ancestors faced in the past environments of South Africa,” said Dr. Justin Adams, an expert in hominin paleoecology at Monash University.

The findings were published in the journal Nature.

_____

Renaud Joannes-Boyau et al. Elemental signatures of Australopithecus africanus teeth reveal seasonal dietary stress. Nature, published online July 15, 2019; doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1370-5