According to a new review of previous studies, published July 29 in the Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, depression is linked to areas of the brain shrinking in size, but when depression is paired with anxiety the part of the brain linked to emotions, the amygdala, becomes larger.

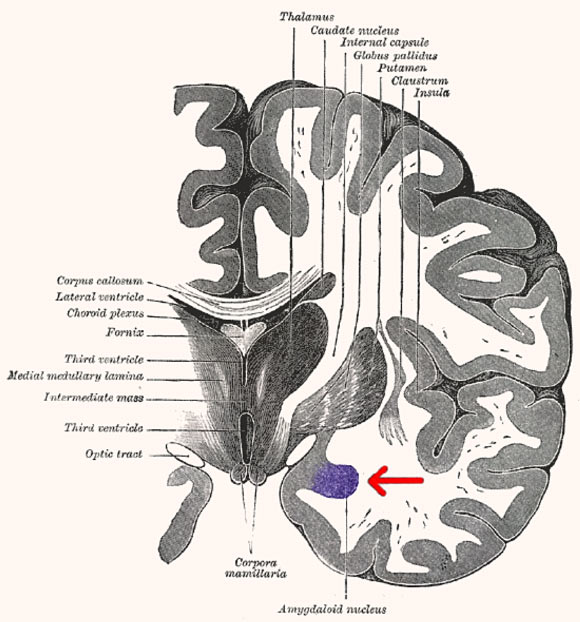

Coronal section of the human brain; amygdala is colored in purple; from Anatomy of the Human Body by Henry Gray.

Globally, depression is the most prevalent and disabling psychiatric disorder. It affects approximately 4.4% of the population, is the leading reason for disease burden and is the fourth leading cause of disability.

The burden and prevalence of depression have increased steadily as a result of population growth and aging given that this trend is expected to continue, it is critical that scientists better understand the neurobiological determinants and progression of depression to improve prevention and management.

Depression is not a uniform disorder, and comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders — most notably anxiety — intrinsically imposes variability on the research.

Anxiety is the second most prevalent psychiatric disorder, and depression comorbid with anxiety has been associated with poorer health outcomes.

“We aimed to provide a comprehensive summary of the literature investigating structural brain changes with depression, considering global and regional volumetric measures using MRI and a specific type of depressive disorder and its different subclassifications to provide a more targeted approach,” said lead author Daniela Espinoza Oyarce, a Ph.D. researcher in the Centre for Research on Ageing, Health and Wellbeing at the Australian National University, and colleagues.

“Crucially and unlike previous reviews, we also comprehensively investigated the effect of comorbidity in an effort to distinguish the contributions of depression from those of anxiety.”

The scientists included 112 studies in their meta-analyses, assessing a total of 10,845 participants (4,911 healthy controls and 5,934 participants with depression; mean age – 49.8 yr, 68.2% female).

Participants with depression and no comorbidity showed significantly lower volumes in the putamen, pallidum and thalamus, as well as significantly lower gray matter volume and intracranial volume; the largest effects were in the hippocampus (6.8%).

Participants with depression and associated anxiety showed significantly higher volumes in the amygdala (3.6%).

“Many studies looking at the effect of depression on brain do not account for the fact that people who have depression often experience anxiety too,” Espinoza Oyarce said.

“We found people who have depression alone have lower brain volumes in many areas of the brain, and in particular the hippocampus.”

“This becomes even more relevant later in life because a smaller hippocampus is a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease and may accelerate the development of dementia.”

“Anxiety lowers the effect of depression on brain volume sizes by three per cent on average — somewhat hiding the true shrinking effects of depression,” she added.

“More research is needed into how anxiety lowers the effects of depression, but for the amygdala, perhaps anxiety leads to overactivity.”

_____

Daniela A. Espinoza Oyarce et al. Volumetric brain differences in clinical depression in association with anxiety: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, published online July 29, 2020; doi: 10.1503/jpn.190156