In a paper in the journal PeerJ, paleontologists report finding a shark tooth embedded in an 80-million-year-old cervical vertebra of the large flying reptile called Pteranodon.

Life reconstruction of a c. 8.2 foot (2.5 m) long breaching Cretoxyrhina mantelli biting the neck of a 16.4 foot (5 m) wingspan Pteranodon longiceps. The predatory behavior of this scene is speculative with respect to the data offered by the 80-million-year-old specimen, but reflects the fact that Cretoxyrhina is generally considered a predatory species, the vast weight advantage of the shark against the pterosaur, and the juvenile impulse of the artist to draw an explosive predatory scene. Image credit: Mark Witton.

In the Late Cretaceous epoch, North America was divided by a giant waterway called the Western Interior Seaway. It was a biologically prolific region from the Gulf of Mexico to Canada.

Some of the world’s best fossils from this time are found here, including the Smoky Hill Chalk region of Kansas, where the newly-described fossil was found.

The specimen was excavated in the 1960s and kept in the Los Angeles County Natural History Museum before University of Southern California’s Dr. Michael Habib and colleagues plucked it from a display for further study.

The scientists were intrigued by the embedded shark tooth because of more than 1,100 specimens of Pteranodon, a large pterodactyloid pterosaur from the Late Cretaceous of North America, only seven (or less than 1%) show evidence of predator-prey interaction.

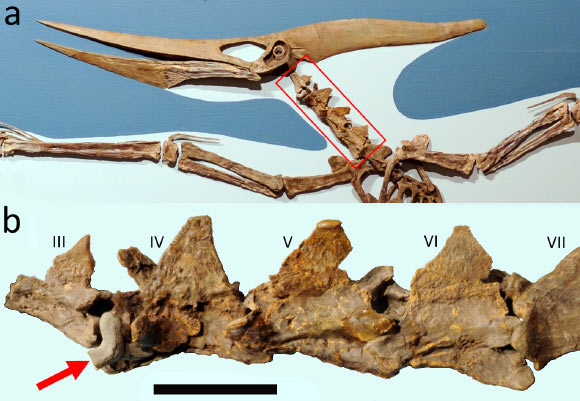

Mounted Pteranodon and close up of the neck: (A) mounted Pteranodon sp. skeleton on display in the Los Angeles County Natural History Museum with highlighted section of the vertebrae shown below; (B) close up of the vertebral series and shark tooth (indicated by an arrow). Cervical vertebrae III-VII are indicated. Scale bar is 50 mm — this is an approximate value based on published measurements of the vertebrae. Image credit: Stephanie Abramowicz / Dinosaur Institute, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County / David Hone.

Pteranodons were masters of the sky. These gigantic flying reptiles abounded when dinosaurs walked the Earth.

They ported a conspicuous crested skull, had a wingspan of 18 feet (5.5 m) and weighed about 100 pounds (45 kg). They could travel long distances, land and take off in water and had a fancy for fish.

But Cretaceous oceans were a dangerous place to linger. Under the waves lurked big, flesh-eating reptiles and sharks.

But which sea monster killed it? How did it happen? And why was the neck bone intact?

First, the paleontologists had to rule out that the shark tooth, about 1 inch (2.5 cm) long, wasn’t randomly stuck to the Pteranodon vertebra; perhaps had both been deposited in a prehistoric boneyard at the same time.

They found that the tooth was stuck between ridges in the neck vertebrae, which was clear evidence of a bite.

The tooth belonged to a large mackerel shark called Cretoxyrhina mantelli. This particular predator was large, fast and powerful, about 8 feet (2.4 m) long and roughly comparable in appearance and behavior to today’s great white shark, though it’s not closely related.

Second, the team wondered why the evidence of attack was preserved at all.

Typically, heavy shark bites utterly shattered pterosaur bones, leaving little trace. In this instance, the tooth just happened to get stuck on a particularly bony part of the neck, which led to the fortuitous fossil.

Such a fossil discovery is so rare that this is the first documented occurrence of this shark species interacting with a pterosaur.

Third, while the researchers may never know exactly what happened, it’s possible the attack occurred when the Pteranodon was most vulnerable, sprawled atop the water.

While Pteranodon could land and take off on water, they were ungainly at sea and took considerable time to take off.

“Understanding the ecology of these animals is important to understanding life on Earth through time,” Dr. Habib said.

“Are there sharks today that hunt seabirds? Yes, there are. Is that unique or have big sharks been hunting flying creatures for millions of years? The answer is yes, they have.”

“We now know sharks were hunting flying animals as long ago as 80 million years.”

_____

D.W.E. Hone et al. 2018. Evidence for the Cretaceous shark Cretoxyrhina mantelli feeding on the pterosaur Pteranodon from the Niobrara Formation. PeerJ 6: e6031; doi: 10.7717/peerj.6031