For several decades, scientists have wondered how Pleistocene ecosystems (2.5 million to 11,700 years ago) survived despite the presence of huge herbivores, such as mammoths, mastodons and giant ground sloths. Now, a team of researchers – led by a scientist from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) – argues that the ecosystems were effectively saved by enormous predators (hyper-carnivores) that helped keep the population of large plant-eaters in check.

A British Pleistocene landscape during an interglacial with cave lion (Panthera spelaea), straight-tusked elephants (Palaeoloxodon antiquus), narrow-nosed rhinoceros (Stephanorhinus hemitoechus), steppe bison (Bison priscus), aurochs (Bison primigenius) and hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius). Image credit: Roman Uchytel, via the Netherlands Institute of Ecology.

Using several different techniques and data sources, Prof. Blaire Van Valkenburgh of UCLA’s Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and her colleagues from the United States, South Africa and the UK, have found that the hyper-carnivores (such as lions, saber-tooth cats and hyenas) were very capable of killing young mammoths, mastodons and other species.

Their findings are reported in a paper published online by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on October 26, 2015.

“Based on observations of living giant herbivores, such as elephants, rhinos, giraffes and hippos, scientists have generally thought that these species were largely immune to predation, mainly because of their large size as adults and strong maternal protection of very young offspring,” Prof. Van Valkenburgh said.

“Data on modern lion kills of elephants indicates that larger prides are more successful and we argue that Pleistocene carnivore species probably formed larger prides and packs than are typically observed today — making it easier for them to attack and kill fairly large juveniles and young adult huge herbivores.”

Based on a series of mathematical models for the sizes of predators and prey in the late Pleistocene age, the scientists conclude that the largest cave hyena might have been able to take down a 5-year-old juvenile mastodon weighing more than a ton.

“Hunting in packs, those hyenas could possibly bring down a 9-year-old mastodon weighing two tons,” Prof. Van Valkenburgh and co-authors said.

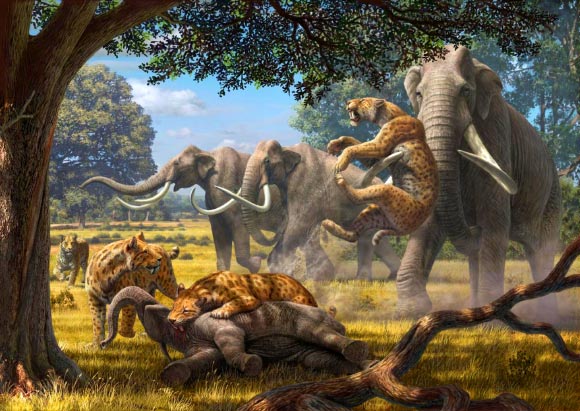

A pack of saber-tooth cats (Smilodon) fight with adult Colombian mammoths over a juvenile mammoth they’ve felled. Image credit: Mauricio Anton.

Their analysis estimated size ranges for Pleistocene predators based on the fossil record, including teeth. Well-established formulas allow scientists to make a reasonable estimate of an animal’s size based on just the first molar.

“And in the fossil record, the one thing we’ve got a lot of is teeth,” Prof. Van Valkenburgh said.

The team developed formulas for the relationship of shoulder height to body mass from data published for modern captive elephants to estimate how large some of the herbivores found in fossil evidence would have been.

“It’s hard to weigh an elephant; you need a truck scale. And truck scales aren’t the easiest thing to lug around the African savannah, so field researchers monitor shoulder heights in tracing a growing elephant’s size,” said co-author Dr V. Louise Roth of Duke University.

“The difficulty is that, even with the best measurements, modern adult elephants with the same shoulder height may vary by as much as two times in body mass.”

Nonetheless, the team developed a range for what some of these shaggy plant-eaters would weigh. From this, they calculated whether hyper-carnivores might be able to capture an herbivore.

Because there is no way to infer from the scant fossil evidence whether the carnivores hunted in packs, the scientists relied on estimated prey sizes and modeled the capacity of single predators and predators in groups to take them down. They conclude that juvenile mastodons and mammoths would indeed have been susceptible, especially if the carnivores were socially organized.

Hunting in packs – as modern lions, hyenas and wolves still do – would have made even larger juveniles susceptible.

“Larger pack sizes, which may have been more common in the Pleistocene, further enhance hunting success,” Prof. Van Valkenburgh said.

Saber-tooth cats (Smilodon) working together may have been capable of taking down juveniles of the largest Pleistocene herbivores, such as this young hippo. Image credit: Mauricio Anton.

Many scientists had thought that the populations of mammoths, mastodons and giant ground sloths were limited through evolution by changes in reproductive timing in response to shortages in resources like food and water.

Today’s large predators benefit their ecosystems in part by providing carcasses that feed an array of smaller species.

“The same was true during the Pleistocene, when keeping mega-herbivore populations in check meant that there was more vegetation for smaller mammals and birds,” the scientists said.

“The predators might even have had indirect effects on river ecosystems, because the banks of the rivers were not being denuded by mega-herbivores and less likely to erode.”

_____

Blaire Van Valkenburgh et al. The impact of large terrestrial carnivores on Pleistocene ecosystems. PNAS, published online October 26, 2015; doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502554112