A newly discovered fossil of an early ray-finned fish, named Saurichthys curionii, from the Middle Triassic of Switzerland reveals a previously unknown mechanism of axial skeleton elongation.

The extreme elongation of body axis occurred in one of two ways: through the elongation of the individual vertebrae of the vertebral column; or through the development of additional vertebrae and associated muscle segments.

Unlike other known fish with elongate bodies, the vertebral column of Saurichthys does not have one vertebral arch per myomeric segment, but two, which is unique. This resulted in an elongation of the body and gave it an overall elongate appearance.

“This evolutionary pattern for body elongation is new,” said Dr Erin Maxwell from the University of Zurich, lead author of the paper published in Nature Communications.

“Previously, we only knew about an increase in the number of vertebrae and muscle segments or the elongation of the individual vertebrae.”

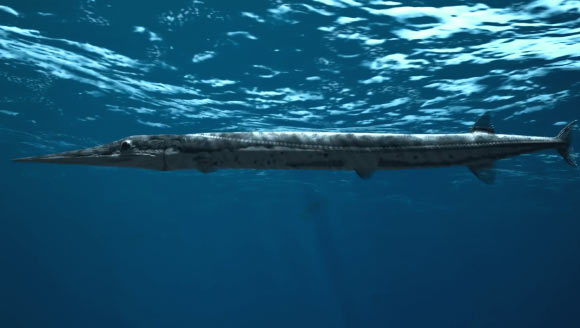

According to Dr Maxwell and his colleagues, Saurichthys was certainly not as flexible as today’s eels and, unlike modern oceanic fishes such as tuna, was probably unable to swim for long distances at high speed.

Based upon its appearance and lifestyle, the roughly half-meter-long fish is most comparable to the garfish or needlefish that exist today.

______

Bibliographic information: Erin E. Maxwell et al. 2013. Exceptional fossil preservation demonstrates a new mode of axial skeleton elongation in early ray-finned fishes. Nature Communications 4, article number: 2570; doi: 10.1038/ncomms3570