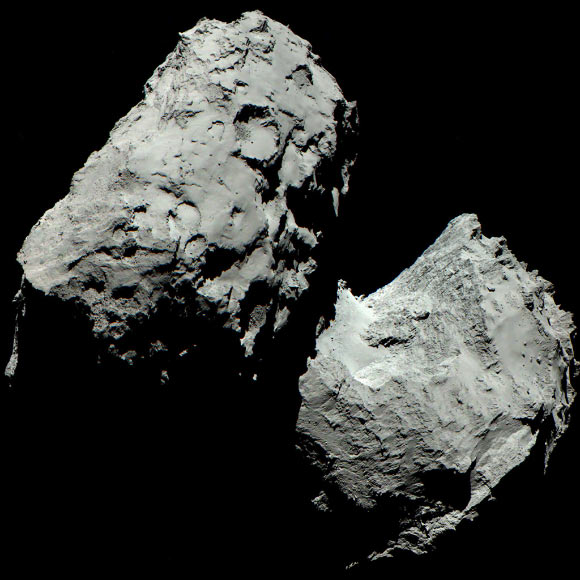

The European Space Agency has released a color image of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko – the prime target of the Rosetta space mission – as it would be seen by the human eye.

A color image of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko composed of three images taken by Rosetta’s scientific imaging system OSIRIS in the red, green and blue filters; the images were taken on August 6, 2014 from a distance of 120 km from the comet. Image credit: ESA / Rosetta / MPS / OSIRIS Team / UPD /LAM / IAA / SSO / INTA / UPM / DASP / IDA.

“As it turns out, 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko looks dark grey, in reality almost as black as coal,” said Dr Holger Sierks of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research.

To create an image revealing comet’s true colors, Dr Sierks and his colleagues superposed images taken by Rosetta’s OSIRIS camera instrument sequentially through filters centered on red, green, and blue wavelengths.

“We like to refer to OSIRIS as the eyes of Rosetta. However, these eyes are quite unlike our own,” Dr Sierks said.

The intensity of the OSIRIS images has been enhanced to span the full range from black to white, in order to make surface details visible.

But the colors have not been enhanced: 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko really is very grey.

At the same time, first analyses show that the comet reflects red light slightly more efficiently than other wavelengths.

This is a phenomenon well-known from many other small bodies and due to the small size of the surface grains. It does not, however, mean that the comet looks reddish to the human eye.

Since in natural sunlight red components are slightly suppressed, to the human eye both effects together create a grayish appearance.

Long before Rosetta’s arrival at 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, ground-based telescope observations had shown the comet to be grey on average, but it was not possible to resolve the comet and see any surface details.

However, now that OSIRIS is able to take images from close-up, researchers are surprised to see an extremely homogeneously colored body even on a detailed scale, pointing at little or no compositional variation on the comet’s surface.

The overall grey color of the surface shows that it is covered some kind of dark dust.

Further studies will focus on trying to understand the composition of this dust, by looking for different minerals such as pyroxenes, common in the Earth’s crust, or minerals containing water.

OSIRIS will also be trying to detect various gas species in the coma surrounding the nucleus.