Astronomers using NASA’s HERSCHEL (Helium Resonance Scattering in the Corona and Heliosphere) sounding rocket have obtained global images of the helium and hydrogen emission in the solar corona, the outermost part of the Sun’s atmosphere. The HERSCHEL observations show that the helium abundance is shaped according to the structure of the large-scale coronal magnetic field and that helium is almost completely absent in the equatorial regions during the quiet Sun.

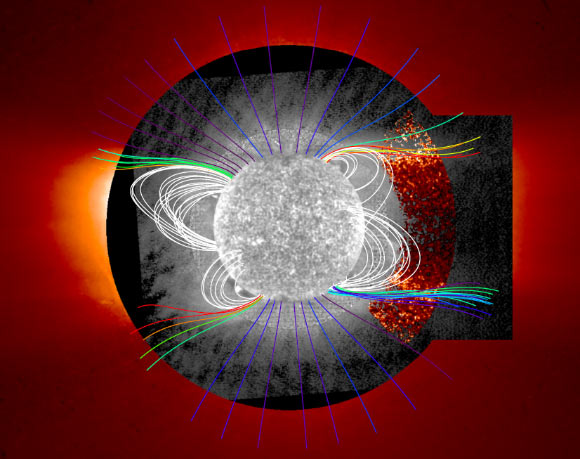

This composite image shows the Sun with open magnetic field lines (colored) overlapping with regions with enhanced helium abundance. Image credit: NASA.

Helium is the second most abundant element in the Universe after hydrogen. But scientists aren’t sure just how much there actually is in the Sun’s atmosphere, where it is hard to measure.

Knowing the amount of helium in the solar atmosphere is important to understanding the origin and acceleration of the solar wind — the constant stream of charged particles from the Sun.

Previously, when measuring ratios of helium to hydrogen in the solar wind as it reaches Earth, observations have found much lower ratios than expected.

Astronomers suspected the missing helium might have been left behind in the solar corona or perhaps in a deeper layer.

“The HERSCHEL sounding rocket investigation adds to a body of work seeking to understand the origin of the slow component of the solar wind,” the astronomers said.

“HERSCHEL remotely investigates the elemental composition of the region where the solar wind is accelerated, which can be analyzed in tandem with in situ measurements of the inner Solar System, such as those of NASA’s Parker Solar Probe.”

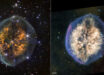

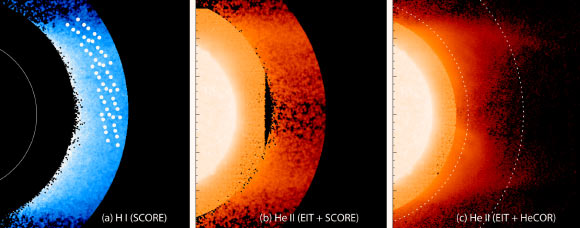

This composite image shows hydrogen (left) and helium (center and right) in the low corona of the Sun. The helium at depletion near the equatorial regions is evident. Image credit: NASA.

The HERSCHEL sounding rocket payload was launched on September 14, 2009 from the White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico, and achieved 397.4 s of observations.

“The HERSCHEL observations showed that helium wasn’t evenly distributed around the corona,” the researchers said.

“The equatorial region had almost no helium while the areas at mid latitudes had the most.”

Comparing with images from the ESA/NASA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), the scientists were able to show the abundance at the mid latitudes overlaps with where Sun’s magnetic field lines open out into the Solar System.

This shows that the ratio of helium to hydrogen is strongly connected with the magnetic field and the speed of the solar wind in the corona.

The equatorial regions, which had low helium abundance measurements, matched measurements from the solar wind near Earth.

This points to the solar atmosphere being more dynamic than the scientists thought.

“While the heat of the Sun is enough to power the lightest element — ionized hydrogen protons — to escape the Sun as a supersonic wind, other physics must help power the acceleration of heavier elements such as helium,” the authors said.

“Thus, understanding elemental abundance in the Sun’s atmosphere, provides additional information as we attempt to learn the full story of how the solar wind is accelerated.”

The results were published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

_____

J.D. Moses et al. Global helium abundance measurements in the solar corona. Nat Astron, published online July 27, 2020; doi: 10.1038/s41550-020-1156-6

This article is based on text provided by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.