The cat tongue is covered in sharp, rear-facing spines called papillae, the precise function of which is a mystery. In a combined experimental and theoretical study, researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology explored how cats groom fur using these fine structures.

Dr. Noel and Dr. Hu discover structures on the cat tongue, hollow spines that they call cavo papillae, shared across six species of cats. Image credit: Pavel Kessa.

Domestic cats, which sleep on average 14 hours each day, spend up to a quarter of their waking hours grooming, which removes fleas, debris, and excess heat from fur.

Cats’ tongues are carpeted with hundreds of sharp spines, which are composed of keratin and spring into action during grooming.

“The cat tongue is most recognized for its hundreds of sharp, backward-facing keratin spines called filiform papillae,” said Georgia Tech scientists Alexis Noel and David Hu.

“A 1982 study concluded that a cat papilla has the shape of a solid cone, an observation that remained undisputed for two decades.”

“In our study, we show that the papilla is in fact scoop shaped, enabling it to use surface tension forces to wick saliva.”

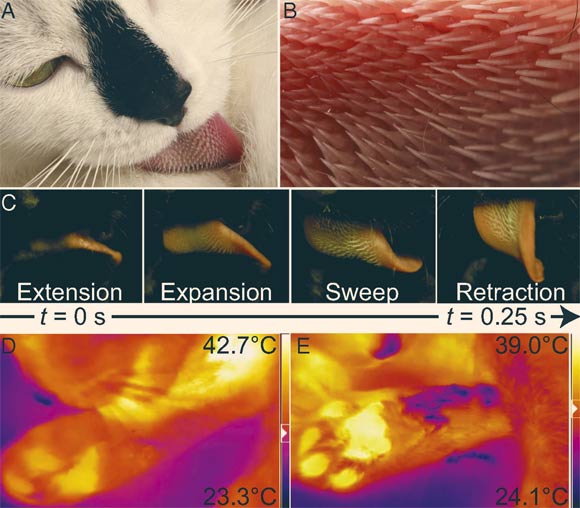

Kinematics of cat grooming: (A) a domestic cat grooms its fur; (B) close-up view of its tongue showing the anisotropic papillae, which point to the left toward the throat; (C) the four phases of cat grooming; (D and E) thermal images of a cat grooming its leg; white colors are hottest and dark blue colors are coolest as shown by the legend on the right; during the groom (D), fur is separated by the motion of the tongue, exposing the skin; heat from the tongue and the skin are indicated by the white color; after the groom (E), evaporation causes a temperature drop of 17 degrees Celsius as shown by the dark purple. Image credit: Noel & Hu, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1809544115.

The researchers used high-speed videos, CT scans, and grooming force measurements to explore how papillae aid grooming in tongue tissues from six cat species: domestic cat, bobcat, cougar, snow leopard, tiger, and lion.

Experiments revealed that U-shaped hollows at the tips of papillae wick saliva from the mouth, each wicking action capturing up to 4.1 μL of saliva, tantamount to one-tenth of the drop of a typical eyedropper.

Each lick of the tongue deposits nearly 50% of the fluid on the tongue onto fur and can deliver a substantive fraction of the cooling effect required for regulating body temperature.

Further, the ease of grooming depends on whether papillae can penetrate fur to reach the skin, explaining why some types of domestic cats, such as long-haired Persian cats, are covered in fur that mats easily and is notoriously difficult to groom.

Using the insights, the team fashioned a cat-tongue-inspired hairbrush that is easier to clean than human hairbrushes.

“Biologically inspired hairbrush might prove a handy implement to remove allergens from cat fur and apply cleaning lotions and medications on cat skin,” Dr. Noel and Dr. Hu said.

The study is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.

_____

Alexis C. Noel & David L. Hu. Cats use hollow papillae to wick saliva into fur. PNAS, published online November 19, 2018; doi: 10.1073/pnas.1809544115