Rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) who learned how to gamble have helped neuroscientists locate an area of the brain linked to risky behavior. The findings, published in the journal Current Biology, could lead to better treatments for destructively risky behaviors in humans.

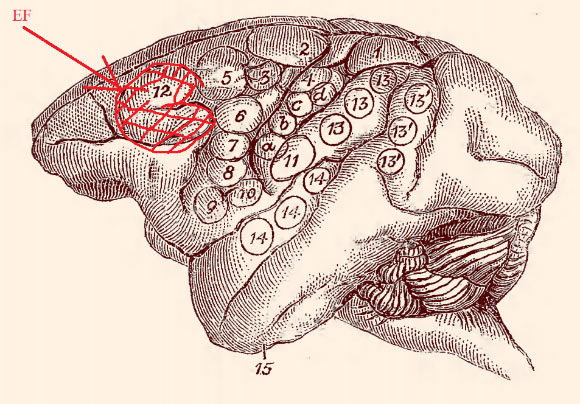

Dr. David Ferrier’s monkey brain map, 1874: the highlighted area labeled ‘EF’ is the area he observed to cause eye and head movements when electrically stimulated.

“People think risk attitude is always the same for individuals, but behavior researchers have found this isn’t true — a person can be risk-averse for some things but inclined to risk in others, like someone who saves a lot of money but also skydives,” said Dr. Veit Stuphorn, a researcher at the Johns Hopkins University’s Zanvyl Krieger Mind/Brain Institute.

“The change in risk attitude happens in the prefrontal cortex, and our findings for the first time identify one critically important area.”

Dr. Stuphorn and his colleague, Dr. Xiamomo Chen from the Stanford University School of Medicine, trained two rhesus monkeys to gamble against a computer in order to win drinks of water.

It turns out both primates were naturally big risk-takers, consistently preferring against-the-odds gambles with potentially high payoffs over much safer, smaller bets.

“For instance, when they were offered a chance to choose between a 20% chance to get 10 milliliters and an 80% chance of getting just three, they’d go for the big gamble,” Dr. Chen said.

“Even when they were no longer thirsty, the macaques still went for risky bets because they just seemed to like the excitement of a win.”

“The macaques should rationally choose the 3 milliliters, but they always went with the riskier option. They’re like people who like to go to Las Vegas to play the slots, where there’s a very high reward but a very low chance of winning it.”

When the team suppressed the brain region known as the supplementary eye field (SEF) — sandwiched between areas responsible for cognition and higher-order motor control — by temporarily inactivating it, however, the high-risk gambling all but disappeared. Suddenly, the monkeys were 30-40% less likely to take risky bets.

“This was truly unexpected, to find a brain section so specifically tied to risk attitude. The monkey’s preference markedly changed from really liking risk to liking it much, much less,” Dr. Stuphorn said.

Suppressing the SEF region surprisingly had no effect on other aspects of the macaque’s gambling, such as their understanding of the game or the way history factored into their bets.

For instance, if they’d just lost a round, the monkeys remained less likely to place big bets, yet they remained slightly more inclined to gamble if they’d just won.

The key area clearly controlled only the primate’s attraction to big, uncertain rewards, the researchers found.

“Because non-human primates and humans share a similar brain structure, the findings should apply to people, where the neural mechanisms of risk have also been largely unknown,” they said.

_____

Xiaomo Chen et al. Inactivation of Medial Frontal Cortex Changes Risk Preference. Current Biology, published online September 20, 2018; doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.07.043