Scientists have long known that we are overwhelmed by too many choices. Now, Caltech Professor Colin Camerer and co-authors have discovered what’s happening inside our brains.

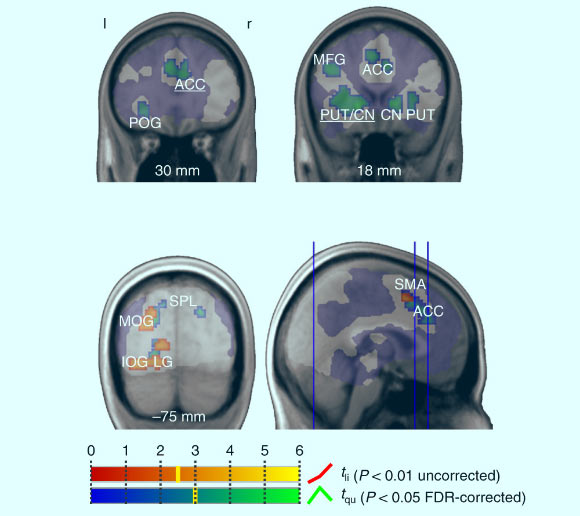

Brain areas reflecting choice set value: areas shown in red to yellow exhibit a linear increase in fMRI activity as a function of S during the exposure stage of the pooled choice trials. Image credit: Reutskaja et al, doi: 10.1038/s41562-018-0440-2.

“In many modern economies consumers have a dizzying variety of choices, even for simple goods like bottled water,” Professor Camerer and colleagues said.

“A typical US supermarket can carry more than 30,000 items, including 285 kinds of cookies and 275 types of cereal. For important lifetime choices, such as decisions about retirement investment, one can be faced with dozens or hundreds of options, with serious consequences if decision making is postponed or avoided entirely.”

“Current models of choice overload mainly derive from behavioral studies. A neuroscientific investigation could further inform these models by revealing the covert mental processes during decision-making.”

“We explored choice overload using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) while subjects were either choosing from varying-sized choice sets or were browsing them.”

In the study, volunteers were presented with pictures of scenic landscapes that they could have printed on a piece of merchandise such as a coffee mug.

Each participant was offered a variety of sets of images, containing six, 12, or 24 pictures.

They were asked to make their decisions while an fMRI machine recorded activity in their brains.

As a control, they were asked to browse the images again, but this time their image selection was made randomly by a computer.

The fMRI scans revealed brain activity in two regions while the participants were making their choices: the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), where the potential costs and benefits of decisions are weighed, and the striatum, a part of the brain responsible for determining value.

Professor Camerer and co-authors also saw that activity in these two regions was highest in subjects who had 12 options to pick from, and lowest in those with either six or 24 items to choose from.

Pattern of activity is probably the result of the striatum and the ACC interacting and weighing the increasing potential for reward (getting a picture they really like for their mug) against the increasing amount of work the brain will have to do to evaluate possible outcomes.

As the number of options increases, the potential reward increases, but then begins to level off due to diminishing returns.

“The idea is that the best out of 12 is probably rather good, while the jump to the best out of 24 is not a big improvement,” Professor Camerer said.

“At the same time, the amount of effort required to evaluate the options increases.”

“Together, mental effort and the potential reward result in a sweet spot where the reward isn’t too low and the effort isn’t too high. This pattern was not seen when the subjects merely browsed the images because there was no potential for reward, and thus less effort was required when evaluating the options.”

“12 isn’t some magic number for human decision-making, but rather an artifact of the experimental design,” he said.

“The ideal number of options for a person is probably somewhere between 8 and 15, depending on the perceived reward, the difficulty of evaluating the options, and the person’s individual characteristics.”

The findings were published in the journal Nature Human Behaviour.

_____

Elena Reutskaja et al. Choice overload reduces neural signatures of choice set value in dorsal striatum and anterior cingulate cortex. Nature Human Behaviour, published online October 1, 2018; doi: 10.1038/s41562-018-0440-2