Paleontologists at the University of Leicester have examined the 150-million-year-old fossilized skeletons of two highly immature Pterodactylus antiquus individuals with broken wings from the Solnhofen Limestones of southern Germany. Their findings show how these creatures were tragically struck down by powerful Jurassic storms that also created the ideal conditions to preserve them and hundreds more fossils like them.

An artist’s impression of a tiny Pterodactylus antiquus hatchling struggling against a raging tropical storm, inspired by fossil discoveries. Image credit: Rudolf Hima.

“The Late Jurassic Solnhofen limestone deposits of Bavaria, southern Germany, dating to 153-148 million years ago, are renowned for their exquisitely preserved fossils, including many specimens of pterosaurs, the flying reptiles of the Mesozoic,” said University of Leicester paleontologist Rab Smyth and colleagues.

“Yet here lies a mystery: while Solnhofen has yielded hundreds of pterosaur fossils, nearly all are very small, very young individuals, perfectly preserved.”

“By contrast, larger, adult pterosaurs are rarely found, and when they are, they’re represented only by fragments (often isolated skulls or limbs).”

“This pattern runs counter to expectations: larger, more robust animals should stand a better chance of fossilization than delicate juveniles.”

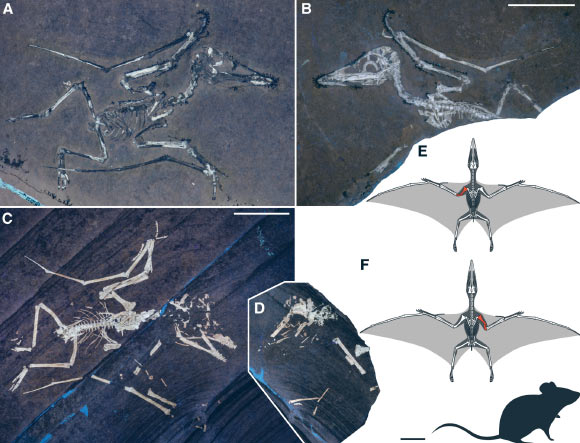

In the new study, the authors analyzed the fossilized skeletons of two immature pterosaurs from the Solnhofen Limestones.

The two individuals belong to Pterodactylus antiquus, a species of pterosaur that lived in what is now Germany during the Kimmeridgian age of the Late Jurassic epoch.

With wingspans of less than 20 cm (8 inches), these hatchlings are among the smallest of all known pterosaurs.

Both show the same unusual injury: a clean, slanted fracture to the humerus.

Neonatal examples of Pterodactylus antiquus from the Solnhofen Limestones, Germany. Scale bars – 20 mm. Image credit: Smyth et al., doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2025.08.006.

The left wing of one individual and the right wing of another were both broken in a way that suggests a powerful twisting force, likely the result of powerful gusts of wind rather than a collision with a hard surface.

Catastrophically injured, the pterosaurs plunged into the surface of the lagoon, drowning in the storm driven waves and quickly sinking to the seabed where they were rapidly buried by very fine limy muds stirred up by the death storms.

This rapid burial allowed for the remarkable preservation seen in their fossils.

Like the two studied pterosaurs, which were only a few days or weeks old when they died, there are many other small, very young pterosaurs in the Solnhofen Limestones, preserved in the same way, but without obvious evidence of skeletal trauma.

Unable to resist the strength of storms these young pterosaurs were also flung into the lagoon.

This discovery explains why smaller fossils are so well preserved — they were a direct result of storms — a common cause of death for pterosaurs that lived in the region.

“For centuries, scientists believed that the Solnhofen lagoon ecosystems were dominated by small pterosaurs,” Dr. Smyth said.

“But we now know this view is deeply biased. Many of these pterosaurs weren’t native to the lagoon at all.”

“Most are inexperienced juveniles that were likely living on nearby islands that were unfortunately caught up in powerful storms.”

A paper on the findings was published today in the journal Current Biology.

_____

Robert S.H. Smyth et al. Fatal accidents in neonatal pterosaurs and selective sampling in the Solnhofen fossil assemblage. Current Biology, published online September 5, 2025; doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2025.08.006