Archaeologists have analyzed a rich microbotanical assemblage from Çatalhöyük, a renowned archaeological site in central Anatolia, Turkey, best known for its Neolithic occupation dated from 7100 to 6000 BCE.

Çatalhöyük, one of the largest and best preserved Neolithic sites in the world, is located southeast of the modern Turkish city of Konya, about 90 miles (145 km) from Mount Hasan.

The site received worldwide attention for its large size, well-preserved mudbrick architecture, and elaborate wall paintings.

Its inhabitants were early farmers, growing crops such as wheat and barley, and herding sheep and goats.

“Despite the extensive research, much of what is known about agricultural practices and the use of plant resources at Çatalhöyük is based on the study of charred remains,” said Universitat Pompeu Fabra researcher Carlos Santiago-Marrero and colleagues.

“However, these remains occur causally, either when cooking food or due to accidental fire, which gives a limited image of the use of plant resources in the past.”

The researchers analyzed microbotanical remains and use-wear traces on the surfaces of grinding tools found at three domestic contexts attributed to the Middle (6700-6500 BCE) and Late (6500-6300 BCE) periods of occupation.

“We recovered residues trapped in the pits and crevices of these stone artifacts that date back to the time of being used, and then carried out studies of microbotanical remains and thus reveal what types of plants had been processed with these artifacts in the past,” they said.

“Among the microscopic remains are phytoliths, from the deposition of opal silica in plant cells and cell walls, that provide clues about the presence of anatomical parts, such as the stems and husks of plants, including wheat and barley.”

“Another residue studied are starches, glucose compounds, created by plants to store energy, which are found in large quantities in many edible parts of plants.”

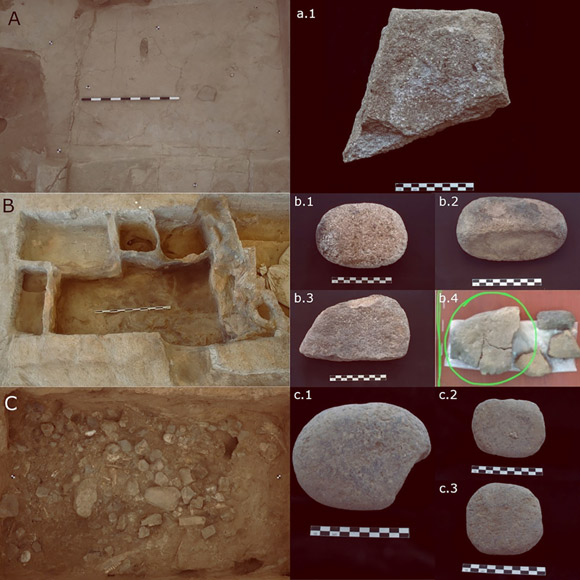

Artifacts and buildings at Çatalhöyük examined by Santiago-Marrero et al.: (A) fixed grinding installation, building 80, space 135; (a.1) quern; (B) storage room with clay bins building 52, space 93; (b.1) grinder; (b.2) grinding/abrasive tool; (b.3) grinding tool; (b.4) grinding slab; (C) artifact cluster building 44, unit 11648; (c.1- c.3) grinders. Image credit: Jason Quinlan, Kate Rose, Uğur Eyilik & Marco Madella, Çatalhöyük Research Project.

They found that the inhabitants of Çatalhöyük cultivated cereals and pulses and collected available wild resources such as fruits and nuts.

“The Çatalhöyük community used a wide range of tuberous plants, many of which belong to potentially toxic taxonomic families and require complex processing or use,” they said.

“This shows the great phytocultural knowledge possessed by this community.”

“Many of these tuberous plants had highly restrictive seasonal life cycles, which helped us to infer the possible means of organizing and exploiting the plant environment at different times of the year.”

“Moreover, another important aspect is the processing of wild millet seeds, which had never been found among the charred remains of plants on the site.”

“By combining microbotanical evidence with use traces, we discovered processes such as grain husking, the milling of legumes, tubers and cereals, and even the use of these implements in other activities not related to plant processing.”

The findings were published in the journal PLoS ONE.

_____

C.G. Santiago-Marrero et al. 2021. A microbotanical and microwear perspective to plant processing activities and foodways at Neolithic Çatalhöyük. PLoS ONE 16 (6): e0252312; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252312