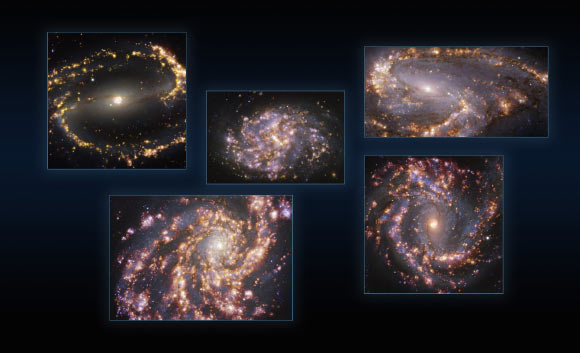

Astronomers know that stars are born in clouds of gas, but what sets off star formation, and how galaxies as a whole play into it, remains a mystery. To understand this process, astronomers have observed five nearby galaxies — NGC 1087, NGC 1300, NGC 3627, NGC 4254, and NGC 4303 — with the Multi-Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE) instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), scanning the different galactic regions involved in stellar births.

This image combines observations of the nearby galaxies NGC 1300, NGC 1087, NGC 3627 (top, from left to right), NGC 4254 and NGC 4303 (bottom, from left to right) taken with the Multi-Unit Spectroscopic Explorer on ESO’s Very Large Telescope. Image credit: ESO / PHANGS.

“For the first time, we are resolving individual units of star formation over a wide range of locations and environments in a sample that well represents the different types of galaxies,” said Dr. Eric Emsellem, an astronomer at ESO and lead of the VLT-based observations conducted as part of the Physics at High Angular resolution in Nearby GalaxieS (PHANGS) project.

“We can directly observe the gas that gives birth to stars, we see the young stars themselves, and we witness their evolution through various phases.”

Dr. Emsellem and colleagues used MUSE to trace newborn stars and the warm gas around them, which is illuminated and heated up by the stars and acts as a smoking gun of ongoing star formation.

By combining MUSE and ALMA images, they can examine the galactic regions where star formation is happening, compared to where it is expected to happen, so as to better understand what triggers, boosts or holds back the birth of new stars.

The resulting images are stunning, offering a spectacularly colorful insight into stellar nurseries in our neighboring galaxies.

“There are many mysteries we want to unravel,” said Dr. Kathryn Kreckel, an astronomer at the University of Heidelberg and a member of the PHANGS team.

“Are stars more often born in specific regions of their host galaxies — and, if so, why? And after stars are born how does their evolution influence the formation of new generations of stars?”

The astronomers will now be able to answer these questions thanks to the wealth of MUSE and ALMA data.

“As amazing as PHANGS is, the resolution of the maps that we produce is just sufficient to identify and separate individual star-forming clouds, but not good enough to see what’s happening inside them in detail,” said Dr. Eva Schinnerer, an astronomer at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy and principal investigator of the PHANGS project.

“New observational efforts by our team and others are pushing the boundary in this direction, so we have decades of exciting discoveries ahead of us.”