Neanderthals and Denisovans are extinct groups of hominins that separated from each other more than 390,000 years ago. These two groups inhabited Eurasia — Neanderthals in the west and Denisovans in the east — until they were replaced by modern humans around 40,000 years ago. Now, a research team led by scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology has sequenced the genome of Denisova 11, a 50,000-year-old individual from Denisova Cave in Siberia, and discovered that she had a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father.

Denisovans were probably dark-skinned, unlike the pale Neanderthals. The picture shows a Neanderthal man. Image credit: Mauro Cutrona.

“We knew from previous studies that Neanderthals and Denisovans must have occasionally had children together,” said co-lead author Dr. Viviane Slon, a researcher in the Department of Evolutionary Genetics at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

“But we never thought we would be so lucky as to find an actual offspring of the two groups.”

The Denisova 11 bone fragment was excavated in 2012 from the East Gallery of Denisova Cave. It weighed 1.68 g, with a maximum length of 24.7 mm and width of 8.39 mm.

“The Denisova 11 individual is only represented by a single small bone fragment,” said co-author Dr. Bence Viola, from the Department of Anthropology at the University of Toronto.

“The fragment is part of a long bone, and we can estimate that this individual was at least 13 years old.”

Dr. Slon, Dr. Viola and their colleagues performed six DNA extractions from bone powder collected from the Denisova 11 specimen, produced ten DNA libraries from the extracts, and sequenced her genome.

To determine from which hominin group Denisova 11 originated, they compared the proportions of DNA fragments that match derived genetic variants from the genome of ‘Altai Neanderthal’ and a Denisovan genome (Denisova 3), both determined from bones discovered in Denisova Cave, as well as from a present-day African genome.

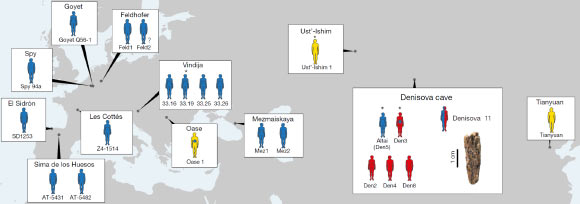

Location of Neanderthals, Denisovans and ancient modern humans dated to approximately 40,000 years ago or earlier. Only individuals from whom sufficient nuclear DNA fragments have been recovered to enable their attribution to a hominin group are shown. Full or abbreviated names of specimens are shown near each individual. Blue – Neanderthals; red – Denisovans; yellow – ancient modern humans. Asterisks indicate that the genome was sequenced to high coverage; individuals with an unknown sex are marked with a question mark. Note that Oase 1 has recent Neanderthal ancestry (blue dot) that is higher than the amount seen in non-Africans. Denisova 3 has also been found to carry a small percentage of Neanderthal ancestry. Image credit: Slon et al, doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0455-x.

“An interesting aspect of the Denisova 11 genome is that it allows us to learn things about two populations — the Neanderthals from the mother’s side, and the Denisovans from the father’s side,” said co-author Dr. Fabrizio Mafessoni, from the Department of Evolutionary Genetics at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

The researchers found that Denisova 11’s father, whose genome bears traces of Neanderthal ancestry, came from a population related to a later Denisovan found in the cave.

The mother came from a population more closely related to Neanderthals who lived later in Europe than to an earlier Neanderthal found in the cave, suggesting that migrations of Neanderthals between eastern and western Eurasia occurred sometime after 120,000 years ago.

“So from this single genome, we are able to detect multiple instances of interactions between Neanderthals and Denisovans,” said co-author Dr. Benjamin Vernot, also from the Department of Evolutionary Genetics at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

“It is striking that we find this Neanderthal/Denisovan child among the handful of ancient individuals whose genomes have been sequenced,” said co-lead author Dr. Svante Pääbo, Director of the Department of Evolutionary Genetics at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

“Neanderthals and Denisovans may not have had many opportunities to meet. But when they did, they must have mated frequently — much more so than we previously thought.”

The findings were published online this week in the journal Nature.

_____

Viviane Slon et al. The genome of the offspring of a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father. Nature, published online August 22, 2018; doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0455-x