Analyses of genome-wide data from 51 Eurasians from 7,000 – 45,000 years ago reveal two big changes in prehistoric human populations that are closely linked to the end of the last Ice Age, approximately 19,000 years ago, according to an international team of researchers led by Harvard Medical School scientist Dr. David Reich.

“Archeological studies have shown that anatomically modern Homo sapiens swept into Europe about 45,000 years ago and caused the demise of Neanderthals, indicated by the disappearance of Neanderthal tools in the archaeological record,” Dr. Reich said.

Scientists also knew that during the Ice Age — a long period of time that ended about 12,000 years ago, with its peak intensity between 25,000 and 19,000 years ago — glaciers covered Scandinavia and northern Europe all the way to northern France.

As the ice sheets retreated beginning 19,000 years ago, prehistoric humans spread back into northern Europe.

But prior to this study, there were only four samples of prehistoric European modern humans 45,000 to 7,000 years old for which genomic data were available, which made it all but impossible to understand how human populations migrated or evolved during this period.

“Trying to represent this vast period of European history with just four samples is like trying to summarize a movie with four still images,” Dr. Reich said.

“With 51 samples, everything changes; we can follow the narrative arc; we get a vivid sense of the dynamic changes over time,” he added.

“And what we see is a population history that is no less complicated than that in the last 7,000 years, with multiple episodes of population replacement and immigration on a vast and dramatic scale, at a time when the climate was changing dramatically.”

The genetic data show that, beginning 37,000 years ago, all Europeans come from a single founding population that persisted through the Ice Age.

The founding population has some deep branches in different parts of Europe, one of which is represented by a specimen from Belgium.

This branch seems to have been displaced in most parts of Europe 33,000 years ago, but around 19,000 years ago, a population related to it re-expanded across Europe.

Based on the earliest sample in which this ancestry is observed, it is plausible that this population expanded from the southwest, present-day Spain, after the Ice Age peaked.

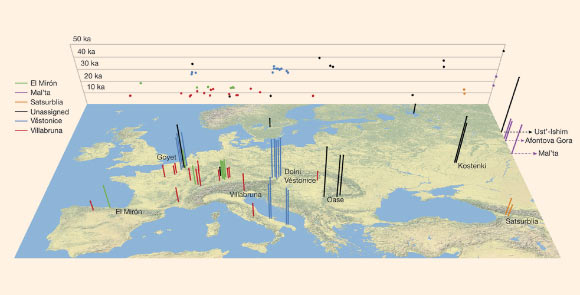

Location and age of the 51 ancient modern humans analyzed in the study: each bar corresponds to an individual, the color code designates the genetically defined cluster of individuals, and the height is proportional to age (the background grid shows a projection of longitude against age). To help in visualization, the scientists added jitter for sites with multiple individuals from nearby locations. Four individuals from Siberia are plotted at the far eastern edge of the map. Image credit: Qiaomei Fu et al.

The second event that Dr. Reich and his colleagues detected happened 14,000 years ago.

“We see a new population turnover in Europe, and this time it seems to be from the east, not the west,” Dr. Reich said.

“We see very different genetics spreading across Europe that displaces the people from the southwest who were there before. These people persisted for many thousands of years until the arrival of farming.”

They also detected some mixture with Neanderthals, around 45,000 years ago, as modern humans spread across Europe.

The prehistoric human populations contained three to 6% of Neanderthal DNA, but today most humans only have about 2%.

“Neanderthal DNA is slightly toxic to modern humans. This study provides evidence that natural selection is removing Neanderthal ancestry,” Dr. Reich said.

The results were published online this week in the journal Nature.

_____

Qiaomei Fu et al. The genetic history of Ice Age Europe. Nature, published online May 2, 2016; doi: 10.1038/nature17993