Trap feeding and tread-water feeding are whale hunting strategies first recorded in the 2000s in two whale species at opposite sides of the globe. In both behaviors, whales sit motionless at the surface with their mouths open. Fish are attracted into the whale’s mouth and are trapped when the jaw is closed. Flinders University maritime archaeologist John McCarthy and his colleagues identified striking parallels with the behavior of a sea creature named hafgufa in Old Norse sources. The hafgufa tradition can be traced back to the aspidochelone, a type of whale frequently described in medieval bestiaries, first appearing in the Physiologus, a 2nd century CE Alexandrian manuscript.

A digital reconstruction of a humpback whale trap feeding. Image credit: McCarthy et al., doi: 10.1111/mms.13009.

Whales are known lunge at their prey when feeding, but recently whales have been spotted at the surface of the water with their jaws open at right angles, waiting for shoals of fish to swim into their mouths.

This strategy seems to work for the whales because the fish think they have found a place to shelter from predators, not realising they are swimming into danger.

It’s not known why this strategy has only recently been identified, but marine scientists speculate that it’s a result of changing environmental conditions — or that whales are being more closely monitored than ever before by drones and other modern technologies.

“I first noticed intriguing parallels between marine biology and historical literature while reading about Norse sea monsters,” Dr. McCarthy said.

“It struck me that the Norse description of the hafgufa was very similar to the behaviour shown in videos of trap feeding whales, but I thought it was just an interesting coincidence at first.”

“Once I started looking into it in detail and discussing it with colleagues who specialise in medieval literature, we realised that the oldest versions of these myths do not describe sea monsters at all, but are explicit in describing a type of whale.”

“That’s when we started to get really interested. The more we investigated it, the more interesting the connections became and the marine biologists we spoke to found the idea fascinating.”

“Old Norse manuscripts describing the creature date from the 13th century and name the creature as a hafgufa.”

“This creature remained part of Icelandic myths until the 18th century, often included in accounts alongside the more infamous kraken and mermaids.”

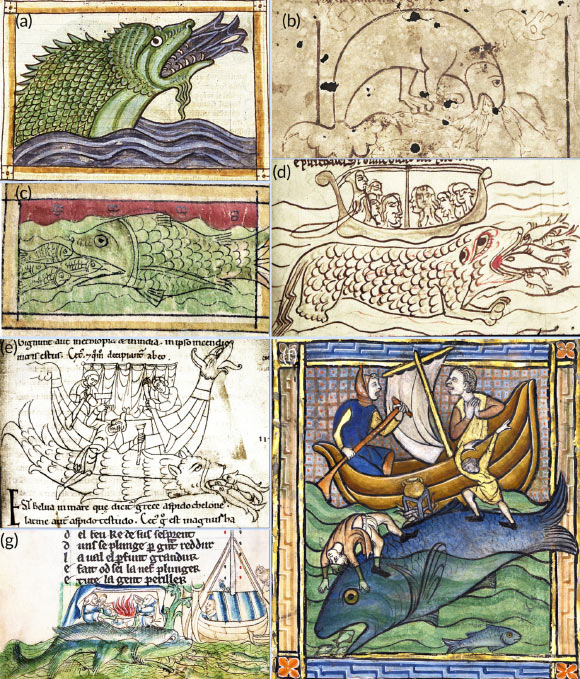

Details of known or suspected aspidochelones in selected medieval manuscripts. Image credit: McCarthy et al., doi: 10.1111/mms.13009.

However, it appears the Norse manuscripts may have drawn on medieval bestiaries, a popular type of text in the medieval period.

Bestiaries describe large numbers of real and fantastical animals and often include a description of a creature very similar to the hafgufa, usually named as the aspidochelone.

Both the hafgufa and aspidochelone are sometimes said to emit a special perfume or scent that helps to draw the fish towards their stationary mouths.

Although some whales produce ambergris, which is an ingredient of perfume, this is not true of such rorquals as the humpback.

Instead, this element may have been inspired by the ejection of filtered prey by whales, to help attract more prey into a whale’s mouth.

“This may be another example of accurate knowledge about the natural environment preserved in forms that pre-date modern science,” said Dr. Erin Sebo, also from Flinders University.

“It’s exciting because the question of how long whales have used this technique is key to understanding a range of behavioral and even evolutionary questions.”

“Marine biologists had assumed there was no way of recovering this data but, using medieval manuscripts, we’ve been able to answer some of their questions.”

“We found that the more fantastical accounts of this sea monster were relatively recent, dating to the 17th and 18th centuries and there has been a lot of speculation amongst scientists about whether these accounts might have been provoked by natural phenomena, such as optical illusions or under water volcanoes.”

“In fact, the behavior described in medieval texts, which seemed so unlikely, is simply whale behavior that we had not observed but medieval and ancient people had.”

The team’s paper was published in the journal Marine Mammal Science.

_____

John McCarthy et al. Parallels for cetacean trap feeding and tread-water feeding in the historical record across two millennia. Marine Mammal Science, published online February 28, 2023; doi: 10.1111/mms.13009