According to a study published in the journal Geology, samples of glassy slabs found in the Atacama Desert, northern Chile, contain tiny fragments with minerals often found in rocks of extraterrestrial origin; those minerals closely match the composition of material returned to Earth by NASA’s Stardust mission, which sampled the particles from a comet called Wild 2; those minerals are likely the remains of a cometary body — most likely a comet with a composition similar to Wild 2 — that streamed down after the explosion that melted the sandy surface below.

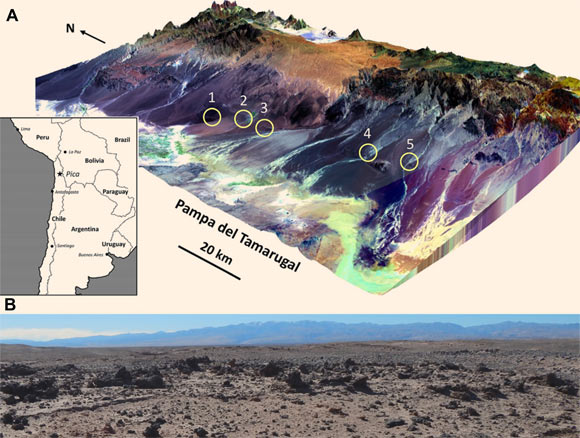

(A) location map for glass localities in Chile: (1) southwest of La Calera; (2) near the town of Pica; (3) Puquio de Núñez; (4) Quebrada de Chipana; and (5) Quebrada Guatacondo. (B) concentration of glassy slabs (dark masses) at the Chipana locality. Largest example in this view is 0.4 m across. Image credit: Schultz et al., doi: 10.1130/G49426.1.

“This is the first time we have clear evidence of glasses on Earth that were created by the thermal radiation and winds from a fireball exploding just above the surface,” said Professor Pete Schultz, a researcher in the Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences at Brown University.

“To have such a dramatic effect on such a large area, this was a truly massive explosion. Lots of us have seen bolide fireballs streaking across the sky, but those are tiny blips compared to this.”

The Pleistocene-epoch silicate glasses were discovered in 2012 in the Atacama Desert along a 75 km north-south corridor, near and southward from the town of Pica.

They occur in five general areas containing innumerable patches, each covering 1 m2 to over 100 m2.

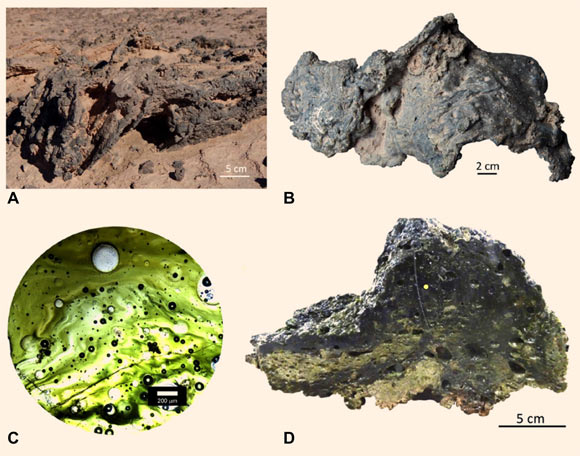

They are characterized by their black/green color. Many have morphologies indicative of sliding, shearing, twisting, rolling, and folding — in some cases, more than twice — before being fully quenched.

As a result, initially flat glassy slabs (5 cm to 7 cm thick) were transformed into large twisted fused masses (up to 50 cm across).

That’s consistent with a large incoming meteor and airburst explosion, which would have been accompanied by tornado-force winds.

(A) example of large glass slab at Chipana (Chile) that folded over during emplacement; (B) twisted glass slab with two contrasting surfaces from Puquio de Núñez: one side is rough with sediments attached; the other side is smooth with flow patterns; contrasting textures indicate formation on a sedimentary surface with subsequent mobilization; (C) thin-section view of folded glass from Puquio de Núñez showing typical green color, vesicles, and schlieren; (D) cut section of large vesicular glass slab with multiple folds that indicate folding while still molten. Image credit: Schultz et al., doi: 10.1130/G49426.1.

“There’s no evidence that the glasses could have been created by volcanic activity, so their origin has been a mystery,” Professor Schultz said.

“Some researchers have posited that the glass resulted from ancient grass fires, as the region wasn’t always desert.”

“During the Pleistocene epoch, there were oases with trees and grassy wetlands created by rivers extending from mountains to the east, and it’s been suggested that widespread fires may have burned hot enough to melt the sandy soil into large glassy slabs.”

“But the amount of glass present along with several key physical characteristics make simple fires an impossible formation mechanism.”

In their research, Professor Schultz and colleagues performed a detailed chemical analysis of dozens of Pica glass samples.

They found minerals called zircons that had thermally decomposed to form baddeleyite.

“That mineral transition typically happens in temperatures in excess of 1,650 degrees Celsius (3,000 degrees Fahrenheit) — far hotter than what could be generated by grass fires,” Professor Schultz noted.

The analysis also turned up assemblages of exotic minerals only found in meteorites and other extraterrestrial rocks.

Specific minerals like cubanite, troilite and calcium-aluminum-rich inclusions matched mineral signatures from comet samples retrieved from NASA’s Stardust mission.

“Those minerals are what tell us that this object has all the markings of a comet,” said Dr. Scott Harris, a planetary geologist at the Fernbank Science Center.

“To have the same mineralogy we saw in the Stardust samples entrained in these glasses is really powerful evidence that what we’re seeing is the result of a cometary airburst.”

_____

Peter H. Schultz et al. Widespread glasses generated by cometary fireballs during the Late Pleistocene in the Atacama Desert, Chile. Geology, published online November 2, 2021; doi: 10.1130/G49426.1