For decades, depictions of Triceratops and its kin have been driven by bone alone. Now, paleontologists in Japan have mapped the soft-tissue anatomy of these horned dinosaurs, revealing unexpected structures that may explain how they regulated temperature and breathed.

Horned dinosaurs (Ceratopsia), including the iconic Triceratops, were among the most diverse and successful dinosaur groups of the Late Cretaceous.

Their skulls rank as some of the most elaborate ever produced by vertebrate evolution, combining the beak, a variety of horns and frills, an expanded nasal region, and a tightly packed dental battery built for processing tough vegetation.

Because these distinctive features likely underpinned the group’s ecological dominance on land, scientists have long focused on the functions of their cranial structures — particularly the horns, beak, and frill.

By contrast, the biological significance of their enlarged nasal region has remained mostly unexamined.

“I have been working on the evolution of reptilian heads and noses since my Master’s degree,” said Dr. Seishiro Tada, a paleontologist at the University of Tokyo Museum.

“Triceratops in particular had a very large and unusual nose, and I couldn’t figure out how the organs fit within it even though I remember the basic patterns of reptiles.”

“That made me interested in their nasal anatomy and its function and evolution.”

In the new study, Dr. Tada and his colleagues examined several cranial specimens of Triceratops.

“Employing X-ray-based CT-scan data of a Triceratops, as well as knowledge on contemporary reptilian snout morphology, we found some unique characteristics in the nose and provide the first comprehensive hypothesis on the soft-tissue anatomy in horned dinosaurs,” Dr. Tada said.

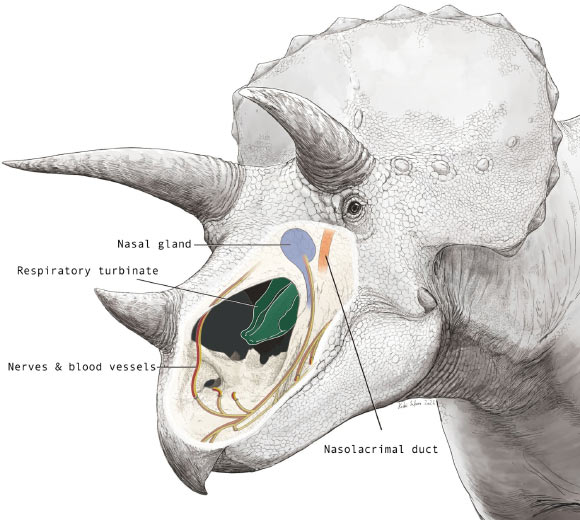

“Triceratops had unusual ‘wiring’ in their noses. In most reptiles, nerves and blood vessels reach the nostrils from the jaw and the nose. But in Triceratops, the skull shape blocks the jaw route, so nerves and vessels take the nasal branch.”

“Essentially, Triceratops tissues evolved this way to support its big nose. I came to realize this while piecing together some 3D-printed Triceratops skull pieces like a puzzle.”

The researchers also identified a specialized structure in Triceratops’ nose known as a respiratory turbinate, an anatomical feature almost unknown among other dinosaurs but common in their living descendants, birds, as well as in mammals.

These thin, curled nasal surfaces increase the contact area between air and blood, helping regulate temperature through heat exchange.

Triceratops probably wasn’t fully warm-blooded, but the scientists think these structures helped keep temperature and moisture levels under control as its large skull would be difficult to cool down otherwise.

“Although we’re not 100% sure that Triceratops had a respiratory turbinate, as most other dinosaurs don’t have evidence for them, some birds have an attachment base (ridge) for the respiratory turbinate and horned dinosaurs have a similar ridge at the similar location in their nose as well,” Dr. Tada said.

“That’s why we conclude they have the respiratory turbinate as birds do.”

“Horned dinosaurs were the last group to have soft tissues from their heads subject to our kind of investigation, so our research has filled the final piece of that dinosaur-shaped puzzle.”

“Next, I would like to tackle questions around the anatomy and function of other regions of their skulls like their characteristic frills.”

The team’s paper was published in the journal Anatomical Record.

_____

Seishiro Tada et al. Nasal soft-tissue anatomy of Triceratops and other horned dinosaurs. Anatomical Record, published online February 7, 2026; doi: 10.1002/ar.70150