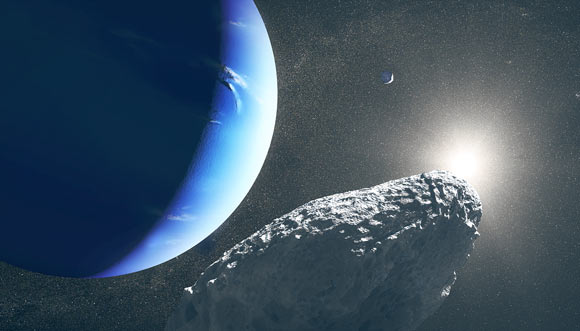

A new study led by SETI Institute astronomers suggests that the recently-discovered moon of Neptune, Hippocamp, is probably an ancient fragment of a much larger neighboring moon, Proteus.

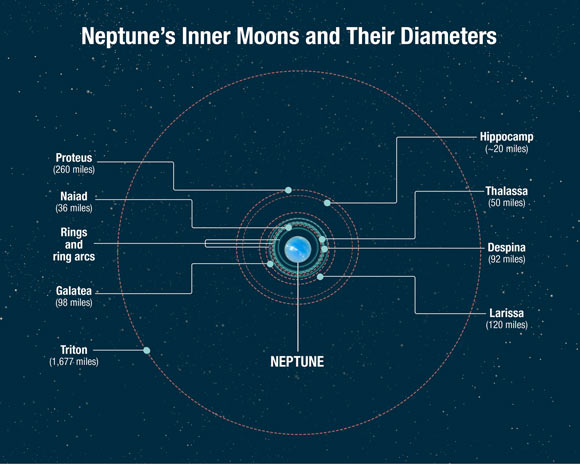

During its 1989 flyby, NASA’s Voyager 2 spacecraft imaged six small moons of Neptune (Naiad, Thalassa, Despina, Galatea, Larissa, and Proteus), all with orbits well interior to that of the large moon Triton.

Along with a set of nearby rings, these inner moons are probably younger than Neptune itself. They formed shortly after the capture of Triton and most of them have probably been fragmented multiple times by cometary impacts.

On July 1, 2013, Dr. Mark Showalter from the SETI Institute discovered a previously unknown seventh inner moon in images taken by the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope.

Named Hippocamp, it is smaller than the other six, with a diameter of 20 miles (34 km).

The tiny moon, also known as S/2004 N 1, is unusually close to the much larger Proteus (260 miles, or 418 km, in diameter).

The orbits of the two moons are presently 7,500 miles (12,070 km) apart.

Normally, a moon like Proteus should have gravitationally swept aside or swallowed the smaller moon while clearing out its orbital path.

So why does the tiny moon exist? According to the new study, Hippocamp is likely a chipped-off piece of Proteus that resulted from a collision with a comet billions of years ago.

This diagram shows the orbital positions of Neptune’s inner moons, which range in size from 20 to 260 miles across. The outer moon Triton was captured from the Kuiper Belt many billions of years ago. This would have torn up Neptune’s original satellite system. Triton settled into a circular orbit and the debris from shattered moons re-coalesced into a second generation of inner satellites seen today. However, comet bombardment continued to tear things up, leading to the birth of Hippocamp, which is a broken-off piece of Proteus. Therefore, it is a third-generation satellite. Not shown is Neptune’s outermost known satellite, Nereid, which is in a highly eccentric orbit, and may be a survivor from the era of that Triton capture. Image credit: NASA / ESA / A. Feild, STScI.

“The first thing we realized was that you wouldn’t expect to find such a tiny moon right next to Neptune’s biggest inner moon,” said Dr. Showalter, lead author of the study.

“In the distant past, given the slow migration outward of the larger moon, Proteus was once where Hippocamp is now.”

This scenario is supported by Voyager 2 images from 1989 that show a large impact crater on Proteus, almost large enough to have shattered the moon.

“In 1989, we thought the crater was the end of the story. With Hubble, now we know that a little piece of Proteus got left behind and we see it today as Hippocamp,” Dr. Showalter said.

“Based on estimates of comet populations, we know that other moons in the outer Solar System have been hit by comets, smashed apart, and re-accreted multiple times,” said co-author Dr. Jack Lissauer, a researcher at NASA’s Ames Research Center.

“This pair of satellites provides a dramatic illustration that moons are sometimes broken apart by comets.”

The study was published in the February 21, 2019 issue of the journal Nature.

_____

M.R. Showalter et al. 2019. The seventh inner moon of Neptune. Nature 566: 350-353; doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0909-9