A new study published in the journal Frontiers in Human Neuroscience shows that the ‘expanding hole’ optical illusion, which is new to science, is perceived by approximately 86% of people.

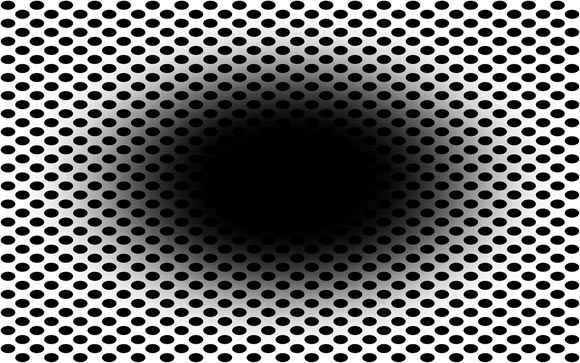

Example of illusorily expanding central region or ‘hole;’ viewing the image full screen is best for eliciting the effect. Image credit: Laeng et al., doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2022.877249.

A large class of optical patterns evoke conscious dynamic sensations of illusory movement, despite being static.

These illusory motions can be described as a variety of changes in shape or space, like drifting, rotating, oscillating, waving, fluttering, contracting, or expanding.

An example of this type of illusion is the ‘expanding hole’ created by Professor Akiyoshi Kitaoka, a co-author of the study and a researcher in the Department of Psychology at Ritsumeikan University.

Typically, when looking at this pattern, observers’ subjective reports are characterized by the perception of a gradually expanding central region, occurring over a span of several seconds.

According to several previous studies, illusions of extent or size are a prominent class. However, classic illusions of size do not evoke dynamic sensations of motion like the ‘expanding hole.’

“The ‘expanding hole’ is a highly dynamic illusion,” said first author Professor Bruno Laeng, a researcher in the Department of Psychology at the University of Oslo.

“The circular smear or shadow gradient of the central black hole evokes a marked impression of optic flow, as if the observer were heading forward into a hole or tunnel.”

Professor Kitaoka, Professor Laeng and their colleague, University of Oslo researcher Shoaib Nabil, found that the ‘expanding hole’ illusion is so good at deceiving our brain that it even prompts a dilation reflex of the pupils to let in more light, just as would happen if we were really moving into a dark area.

“Here we show based on the new ‘expanding hole’ illusion that that the pupil reacts to how we perceive light — even if this ‘light’ is imaginary like in the illusion — and not just to the amount of light energy that actually enters the eye,” Professor Laeng said.

“The illusion of the expanding hole prompts a corresponding dilation of the pupil, as it would happen if darkness really increased.”

In their study, the researchers explored how the color of the expanding hole (besides black: blue, cyan, green, magenta, red, yellow, or white) and of the surrounding dots affect how strongly we mentally and physiologically react to the illusion.

On a screen, they presented variations of the ‘expanding hole’ image to 50 women and men with normal vision, asking them to rate subjectively how strongly they perceived the illusion.

While participants gazed at the image, they measured their eye movements and their pupils’ unconscious constrictions and dilations.

As controls, the participants were shown ‘scrambled’ versions of the expanding hole image, with equal luminance and colors, but without any pattern.

The illusion appeared most effective when the hole was black.

Around 14% of participants didn’t perceive any illusory expansion when the hole was black, while 20% didn’t if the hole was in color.

Among those who did perceive an expansion, the subjective strength of the illusion differed markedly.

The scientists also found that black holes promoted strong reflex dilations of the participants’ pupils, while colored holes prompted their pupils to constrict.

For black holes, but not for colored holes, the stronger individual participants subjectively rated their perception of the illusion, the more their pupil diameter tended to change.

The authors don’t yet know why a minority seem unsusceptible to the ‘expanding hole’ illusion. Nor do they know whether other vertebrate species, or even nonvertebrate animals with camera eyes such as octopuses, might perceive the same illusion as we do.

“Our results show that pupils’ dilation or contraction reflex is not a closed-loop mechanism, like a photocell opening a door, impervious to any other information than the actual amount of light stimulating the photoreceptor,” Professor Laeng said.

“Rather, the eye adjusts to perceived and even imagined light, not simply to physical energy.”

“Future studies could reveal other types of physiological or bodily changes that can ‘throw light’ onto how illusions work.”

_____

Bruno Laeng et al. The Eye Pupil Adjusts to Illusorily Expanding Holes. Front. Hum. Neurosci, published online May 30, 2022; doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2022.877249