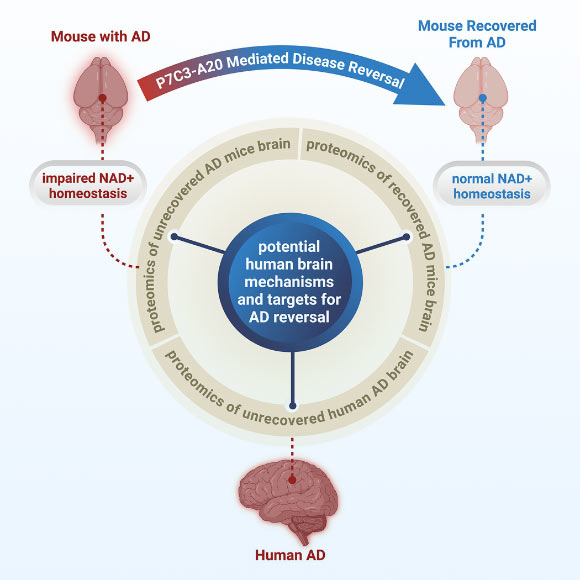

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is traditionally considered irreversible. However, a team of scientists led by Case Western Reserve University, University Hospitals and the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center provided proof of principle for therapeutic reversibility of advanced AD. Using diverse preclinical mouse models and analysis of human AD brains, they showed that the brain’s failure to maintain normal levels of a central cellular energy molecule, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), is a major driver of AD, and that maintaining proper NAD+ balance can prevent and even reverse the disease.

Severity of Alzheimer’s disease correlates with NAD+ homeostasis dysregulation. Image credit: Chaubey et al., doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2025.102535.

AD, commonly considered irreversible since its discovery over a century ago, is the leading cause of dementia and is projected to afflict over 150 million people by 2050.

Current therapies targeting amyloid beta (Aβ) or clinical symptoms offer limited benefit to patients, highlighting the need for complementary and alternative treatments.

Notably, people who carry autosomal dominant AD mutations can remain symptom-free for decades before clinical onset, and some individuals known as nondemented with Alzheimer’s neuropathology accumulate abundant amyloid plaques yet remain cognitively intact.

These findings imply the existence of intrinsic brain resilience mechanisms that delay or counteract disease progression, suggesting the possibility of preserving or enhancing such processes to modify disease trajectory or foster recovery from AD.

NAD+ homeostasis is central to cellular resilience against oxidative stress, DNA damage, neuroinflammation, blood-brain barrier deterioration, impaired hippocampal neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity deficits, and neurodegeneration.

In a new study, Case Western Reserve University’s Professor Andrew Pieper and his colleagues showed that the decline in NAD+ is more severe in the brains of people with AD, and that this same phenomenon also occurs in mouse models of the disease.

While AD is a uniquely human condition, it can be studied in the laboratory with mice that have been genetically engineered to express genetic mutations known to cause AD in people.

The researchers used two of these mouse models: one carried multiple human mutations in amyloid processing; the other carried a human mutation in the tau protein.

Both lines of mice develop brain pathology resembling AD, including blood-brain barrier deterioration, axonal degeneration, neuroinflammation, impaired hippocampal neurogenesis, reduced synaptic transmission and widespread accumulation of oxidative damage.

These mice also develop the characteristics of severe cognitive impairments seen in people with AD.

After finding that NAD+ levels in the brain declined precipitously in both human and mouse AD, the scientists tested whether preventing loss of brain NAD+ balance before disease onset or restoring brain NAD+ balance after significant disease progression could prevent or reverse AD, respectively.

The study was based on their previous work showing that restoring the brain’s NAD+ balance achieved pathological and functional recovery after severe, long-lasting traumatic brain injury.

They restored NAD+ balance by administering a now well-characterized pharmacologic agent known as P7C3-A20.

Remarkably, not only did preserving NAD+ balance protect mice from developing AD, but delayed treatment in mice with advanced disease also enabled the brain to fix the major pathological events driven by the disease-causing genetic mutations.

Moreover, both lines of mice fully recovered cognitive function. This was accompanied by normalized blood levels of phosphorylated tau 217, a recently approved clinical biomarker of AD in people, providing confirmation of disease reversal and highlighting an objective biomarker that could be used in future clinical trials for AD recovery.

“We were very excited and encouraged by our results,” Professor Pieper said.

“Restoring the brain’s energy balance achieved pathological and functional recovery in both lines of mice with advanced AD.”

“Seeing this effect in two very different animal models, each driven by different genetic causes, strengthens the new idea that recovery from advanced disease might be possible in people with AD when the brain’s NAD+ balance is restored.”

The results prompt a paradigm shift in how researchers, clinicians and patients can think about treating AD in the future.

“The key takeaway is a message of hope — the effects of Alzheimer’s disease may not be inevitably permanent,” Professor Pieper said.

“The damaged brain can, under some conditions, repair itself and regain function.”

“Through our study, we demonstrated one drug-based way to accomplish this in animal models, and also identified candidate proteins in the human AD brain that may relate to the ability to reverse AD,” said Dr. Kalyani Chaubey, a researcher at Case Western Reserve University and University Hospitals.

Current over-the-counter NAD+-precursors have been shown in animal models to raise cellular NAD+ to dangerously high levels that promote cancer.

The pharmacological approach in this study, however, uses a pharmacologic agent (P7C3-A20) that enables cells to maintain their proper balance of NAD+ under conditions of otherwise overwhelming stress, without elevating NAD+ to supraphysiologic levels.

“This is an important factor when considering patient care, and clinicians should consider the possibility that therapeutic strategies aimed at restoring brain energy balance might offer a path to disease recovery,” Professor Pieper said.

The findings appear in the journal Cell Reports Medicine.

_____

Kalyani Chaubey et al. Pharmacologic reversal of advanced Alzheimer’s disease in mice and identification of potential therapeutic nodes in human brain. Cell Reports Medicine, published online December 22, 2025; doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2025.102535